|

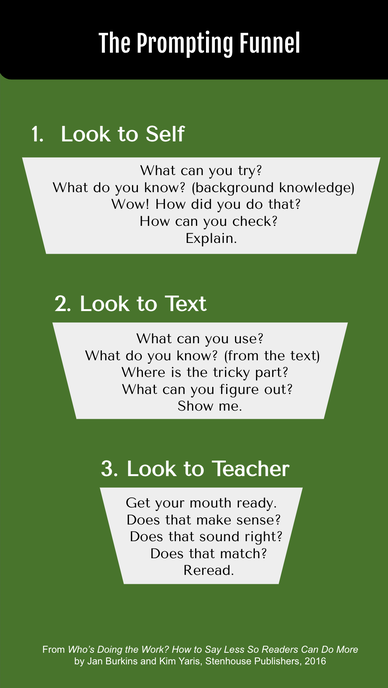

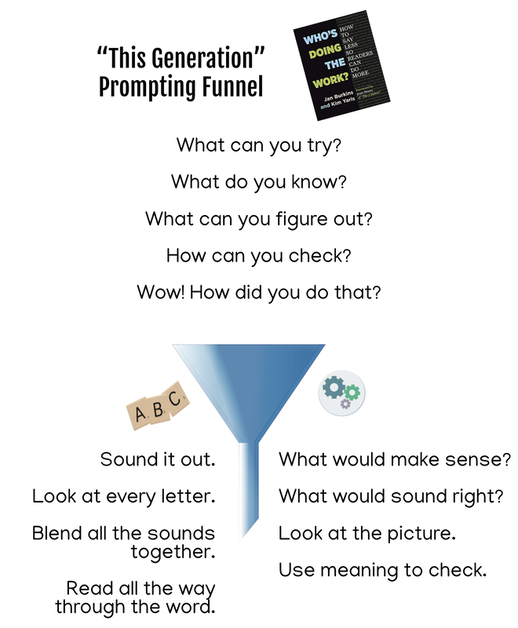

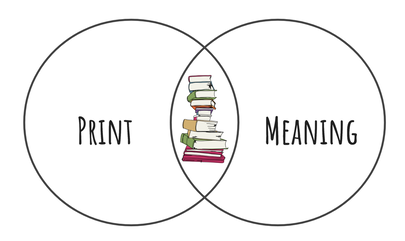

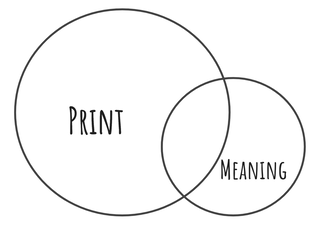

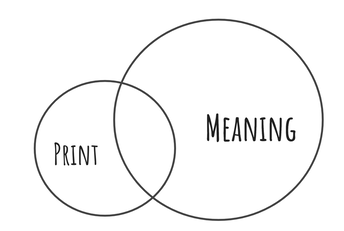

It has been about five years since Kim Yaris and I shared "The Prompting Funnel" in Who's Doing the Work? How to Say Less So Readers Can Do More. The premise of the prompting funnel is that, in the moment of supporting a student at the point of difficulty, our biggest work is actually to not do their work for them! Questions and prompts from the top of the prompting funnel require students to do more of the work, while those at the bottom provide heavier scaffolding. Rather than supporting heavily from the moment a student encounters something tricky, we can save the questions from the bottom of the prompting funnel until students have had time to wrestle with the challenge a bit. The original prompting funnel is below. Predictably, my thinking has evolved and my vision for the prompting funnel has expanded since its inception. More specifically, all of the research that Kari Yates and I did as we were writing our new book, Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading Into the Balanced Literacy Classroom, made it clear that the last stage of the prompting funnel needed refining. More specifically, the prompts at the bottom of the prompting funnel need to be considered based on the particular problem a student is trying to solve. For example, if a child is trying to figure out a word, prompting them to look at the print and say the sounds--and then check with the context--is the "best practice." On the other hand, if a student is trying to figure out the meaning of a word, asking them to check the context is an important bottom-of-the-prompting-funnel cue. Basically, prompts and cues from the bottom of the prompting funnel may vary based on the challenge, whether with the print or with the meaning. This expanded version of the prompting funnel is below. You can download a bookmark of this updated prompting funnel, here. I offer a full explanation of these revisions to the prompting funnel in the new version of the Who's Doing the Work? Online Class. I would love to have you join me for a deeper dive into this versatile and practical tool. The idea behind the prompting funnel can change the way you scaffold students when they encounter the tricky things that are within their grasp and offer them the biggest opportunities for growth.

0 Comments

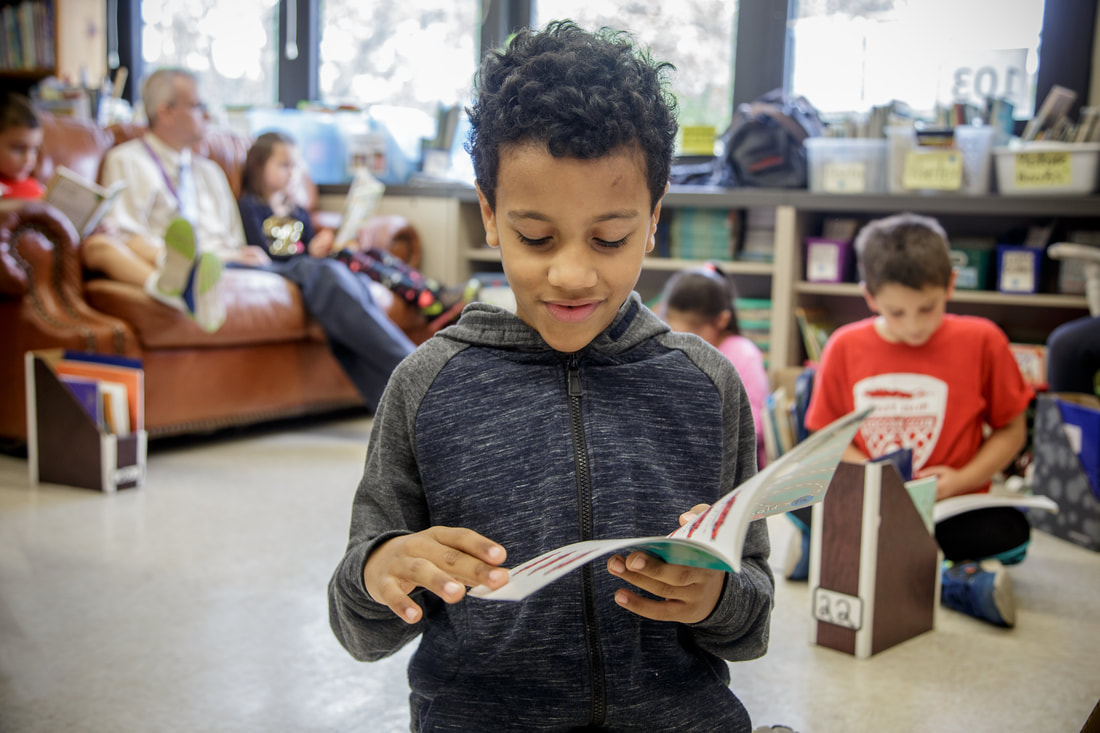

This year, even more than ever, you may be asking, "How do I fit it all in?!" We are, of course, in an unprecedented school year with abundant varieties of scheduling challenges. Whether you are teaching face-to-face or virtually, or in one of the million combinations of the two, you can work with even the trickiest of schedules by first stepping back to think about the big picture of your instruction. There are two common scheduling challenges that can compromise learning in your classroom, and both can be addressed with one, simple strategy. While the solution may not be perfect--there is no "perfect" solution to seeing children only once a week or having only 20 minutes for reading instruction--it will help you keep your focus on the overall goal of your literacy instruction--helping your students become proficient in the ways they navigate the print (phonemes and graphemes) and their ability to construct meaning. The reality is, you can’t fit "it all" in (and never could), as you are already aware--at least on some level. But each morning we begin the day and we try again to fit all the pieces into that six hours with students--or 3 hours, or 2 hours, or even 40 minutes! Inevitably, when our time is crunched, we end up cutting the same things because we have adopted the inaccurate belief that one instructional context is most important. We feel like word work is more important than read aloud, for example, so when the schedule is cut, so is read aloud. This means that our instruction is incomplete. Over time, this can form a pattern that undermines your efforts with students. In truth, your word work time will, in the long run, be much less beneficial for students if they don't get the glorious vocabulary building from read aloud. The second challenge is the temptation to search for a silver bullet or to put all your eggs in one basket; choose your cliche. The tendency to favor an instructional context makes us human, but fortunately we can be systematic in planning how we spend our instructional time. For example, usually when you ask someone who teaches guided reading how they teach reading, they respond by saying that they teach guided reading. The problem with such a response is that it shows an imbalance in instruction. Guided reading was never intended to be a program. It isn’t the core. Guided reading was designed as part of a larger context, which includes independent reading, shared reading, read aloud, and word work. Guided reading is not more important than these other pieces. The tendency is to set up guided reading and let the other pieces fall into place as they do, if they do. A relatively simple (albeit not perfect) solution to both problems of incompleteness and imbalance--which are really just two sides of the same coin--is to plan the instructional week rather than the instructional day. Practically speaking, you can plan with sticky notes and we implement with an egg timer. Planning Assign a sticky notes of a different color to each of the instructional contexts you want to include in your classroom. For example, shared reading may be represented by pink sticky notes, guided reading by yellow sticky notes, independent reading by green sticky notes, etc. Now do the math! Figure out a balance of instructional contexts that really works, in order to give your students a complete learning opportunity. You may only be able to teach guided reading three days a week in order to also read aloud three days a week and engage in shared reading three days a week. In fact, in some of the hybrid models teachers are grappling with right now, you may have to really narrow the amount of time you spend on each instructional context in order to teach all of them. This is, of course, less than ideal, but most of us don't get to decide the limitations on our instructional schedule, only how we spend the time within it. While these kinds of trade-offs may seem scary (and they are when you are trying to teach five instructional contexts in thirty minutes!) they can actually make you more efficient and give you some relief from the guilt of never feeling as if you can fit "it" all in. As you experiment with this shift, you may discover, for example, that much of what you previously accomplished in guided reading may be more efficiently taught in shared. Or you may find that you were teaching every student in small-groups when some don’t need that level of scaffolding. Once you have a week's schedule arranged, look at it as a whole. How balanced are the colors? Of course, this isn’t a rigid strategy. The time doesn’t have to be divided up into exactly equal portions. Things will vary based on the age of children, the point in the school year, etc. In general, however, does the schedule look relatively balanced and relatively complete? Implementation

Once you have a plan, you face the challenge of implementation. Of course, your schedule will vary from day-to-day. Now really concentrate on working within the timeframes. Use an egg timer and stop when you had planned to. This is really challenging, but if you do it a few times you will begin to really think about instructional time. If you know that you can’t run over the allotted time for guided reading, you will find ways to stay on schedule. Also, planning to stop, even if you aren’t finished, means that read aloud, independent reading, etc. don’t get neglected. Of course, this is not meant to be a militaristic implementation. I am not suggesting you teach robotically or become a rigidly driven by the clock. I am suggesting, however, that if you want to fit everything in, you will have to do a bit less of some things and a bit more of others. These kinds of changes in practice requires a shift from the frustrating mental model of fitting everything in every day. You can begin developing a new, kinder mental model with a few pads of sticky notes and an egg timer. Adapted from a blog post originally written by Jan Burkins and Kim Yaris. Like many of us, I have been eager to move past 2020 without really looking back. I usually enjoy beginning each New Year by reflecting on the past year's learning and shaping plans for the next. However, the idea of lingering in the residue of 2020 has been unappealing at best, horrifying at worst. Who really wants to reflect on one of the hardest year's ever?

To complicate the reflective work even more, I tend to judge myself for not having enough pain this year to even really give myself permission to grieve or process it. Certainly, many people have had it much worse than I have. I continue to live a life with much privilege. We do not have hunger or housing insecurity. While 2020 has been challenging professionally, I have managed to keep my work afloat enough to support us. And most significantly, I have not lost a loved one to COVID (or anything else) this year. So what do I really have to lament from 2020? My sweet friend, Krystle Cobran, author of The Brave Educator, once told me, "We have a tendency to compare pain." She went on to say that using someone else's pain to delegitimize our own only delays our healing. So I try to give myself permission to process my experiences, even when some part of my brain tells me that they aren't serious enough to warrant attention because someone else's pain is more. I have learned the truth, however, that I can't be of service to anyone if I haven't tended my own inner garden in ways that are loving. This means acknowledging my hurts and grieving my losses, even if they seem smaller than someone else's. So when another friend, Lizzie Merritt, mentioned that she had just finished her "annual year in review" process, I thought, "Wait a minute! Perhaps, this year needs to be looked at even more closely than usual, rather than boxed up and stored in the recesses of my psychological closet." Lizzie was kind enough to share with me a reflective tool she created for learning from a previous year and planning for a new one. What I love about Lizzie's work is that she seems to really find a balance between action and reflection, between listening to ourselves and engaging our power to move past our limitations. For example, Lizzie's book about willpower begins with recommendations about learning to meditate. Lizzie was kind enough to let me share her year-in-review tool. I found the reflective the process challenging. I was surprised by how tender I was and how much my weary inner self wanted to avoid the work of self-reflection. I worked through the process in four different sittings, which helped. Because my work has demanded so much focus this year, I didn't pick work as a category. Basically, I never need nudging to work more. Instead, I chose: Health and Fitness; Home/Physical Environment; and Fun and Leisure. All of these areas need some serious attention from me. In fact, when I got to "Fun and Leisure," I was stumped (Does working on a "fun" writing project count?). Here's some of what I learned from the whole reflective process:

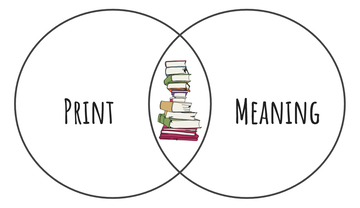

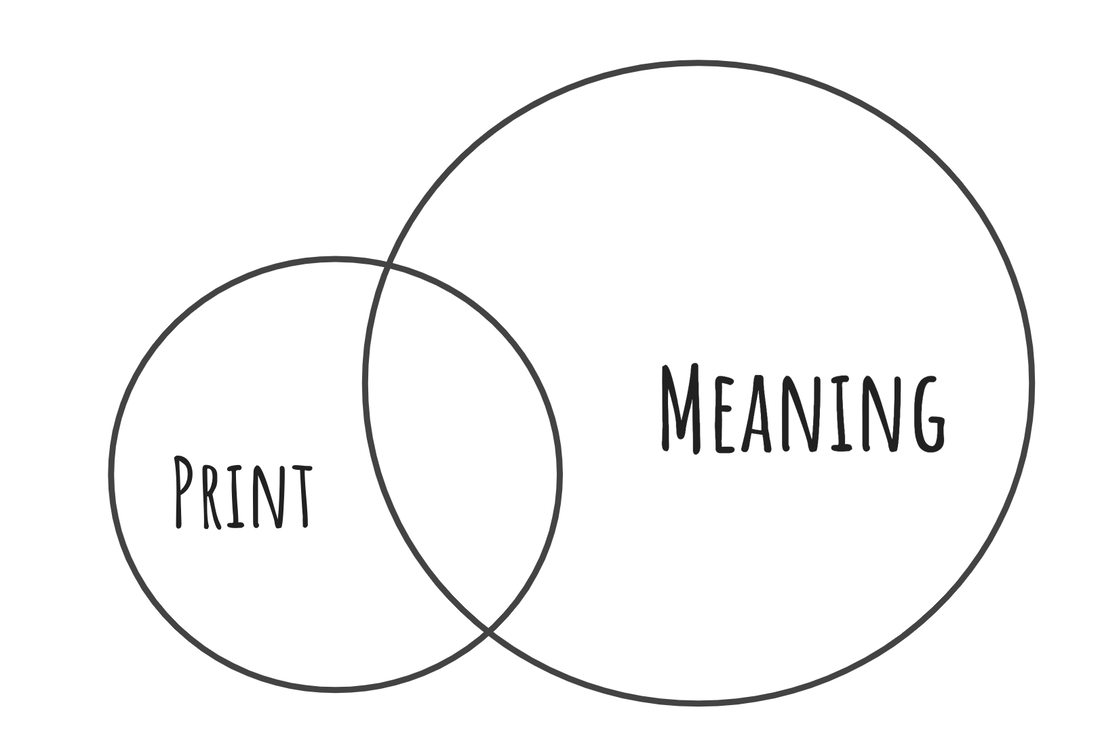

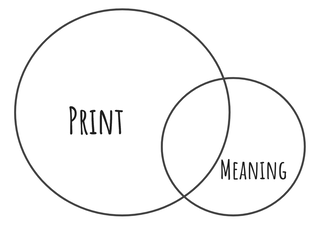

So, while I have no interest in a repeat of 2020, now that it is almost behind me, I am grateful for what it is taught me. May 2021 bring everyone at least some small dose of "normal." May we be kind to ourselves as we process 2020's difficulties, and may or biggest growth work of this year the stay with us, propelling us to be our most powerful selves. In part one of this series, I introduced the following model as a representation of how proficient readers are able to make full use of both the print information and the meaning information in a text. I also described two variations on reading process, which illustrate the ways students may be better at using one or the other source of information.

|

|

|

Missing Socks Look closely! What happened to all the missing socks? Author: Jan Burkins & Kim Yaris Illustrator: Marce Gómez & David Silva Reading Level: A Genre: Fiction |

Here are some highlights from the collection:

|

Back-to-School:

There is one title that is specifically about starting school. It is a Level E text about a peacock who is nervous about the start of school and afraid to display his feathers. When his teacher asks him to introduce himself and share one thing he is good at, he is much too shy. After making friends on the playground, he musters his courage and shows his true self. |

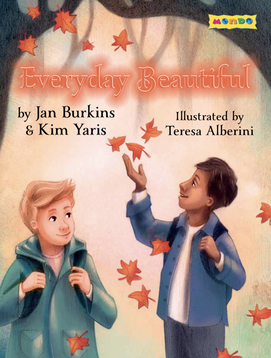

There are three titles in the collection that relate to mindfulness. Happy (Level C) is about a little girl who is exploring different kinds of happiness, such as the calm happiness of a breeze vs. the palpable happiness of a surprise birthday party. Hurry Up, Slow Down (Level D) is about a little girl who is walking to school with her father and is caught up in the simple beauty around her. Finally, Everyday Beautiful (Level H) is about two boys who have been asked to find something beautiful. One boy overlooks the natural beauty around him while another shows him how simple things can be beautiful.

There are five titles in the collection that use science related to light and shadows to tell a story. They range in levels from C-J. We wrote these to align with science standards. If you teach light and shadows, you may find these texts a nice way to integrate your science content into your reading instruction.

If you already have the Who's Doing the Work? K-2 Lesson Sets, these digital versions of some of the books should be helpful. Although you don't need the lessons to use the books, if you are interested in the lessons that go with the books, they are available from Stenhouse Publishers.

Author

Dr. Jan Burkins is a full-time writer, consultant, and professional development provider.

Categories

All

Assessment

Asynchronous

Back To School

Back-to-school

Balance

Balanced Literacy

Beginning Reading

Books

Breathing

Classroom Library

Comprehension

Cue

Decoding

Distance Learning

Educational Technology

Fluency

Free Books

Guided Reading

Hybrid Models

Independent Reading

Mask

Masks

Meaning

Mental Models

Mindfulness

Morphemes

New Year

Personal Growth

Phonemic Awareness

Phonological Awareness

Planning

Preventing Misguided Reading

Print

Prompt

Prompting

Prompting Funnel

Questioning

Racism

Read Aloud

Reading Wars

Reflection

Research

Routines

Schedule

Science Of Reading

Shared Reading

Social Justice

SoR

Sources Of Information

Stories

Synchronous

Technology

Text Selection

The Great Debate

Unit

Virtual

Virtual Guided Reading

Vocabulary Instruction

Wait Time

Whiteness

Who's Doing The Work?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed