|

This year, even more than ever, you may be asking, "How do I fit it all in?!" We are, of course, in an unprecedented school year with abundant varieties of scheduling challenges. Whether you are teaching face-to-face or virtually, or in one of the million combinations of the two, you can work with even the trickiest of schedules by first stepping back to think about the big picture of your instruction. There are two common scheduling challenges that can compromise learning in your classroom, and both can be addressed with one, simple strategy. While the solution may not be perfect--there is no "perfect" solution to seeing children only once a week or having only 20 minutes for reading instruction--it will help you keep your focus on the overall goal of your literacy instruction--helping your students become proficient in the ways they navigate the print (phonemes and graphemes) and their ability to construct meaning. The reality is, you can’t fit "it all" in (and never could), as you are already aware--at least on some level. But each morning we begin the day and we try again to fit all the pieces into that six hours with students--or 3 hours, or 2 hours, or even 40 minutes! Inevitably, when our time is crunched, we end up cutting the same things because we have adopted the inaccurate belief that one instructional context is most important. We feel like word work is more important than read aloud, for example, so when the schedule is cut, so is read aloud. This means that our instruction is incomplete. Over time, this can form a pattern that undermines your efforts with students. In truth, your word work time will, in the long run, be much less beneficial for students if they don't get the glorious vocabulary building from read aloud. The second challenge is the temptation to search for a silver bullet or to put all your eggs in one basket; choose your cliche. The tendency to favor an instructional context makes us human, but fortunately we can be systematic in planning how we spend our instructional time. For example, usually when you ask someone who teaches guided reading how they teach reading, they respond by saying that they teach guided reading. The problem with such a response is that it shows an imbalance in instruction. Guided reading was never intended to be a program. It isn’t the core. Guided reading was designed as part of a larger context, which includes independent reading, shared reading, read aloud, and word work. Guided reading is not more important than these other pieces. The tendency is to set up guided reading and let the other pieces fall into place as they do, if they do. A relatively simple (albeit not perfect) solution to both problems of incompleteness and imbalance--which are really just two sides of the same coin--is to plan the instructional week rather than the instructional day. Practically speaking, you can plan with sticky notes and we implement with an egg timer. Planning Assign a sticky notes of a different color to each of the instructional contexts you want to include in your classroom. For example, shared reading may be represented by pink sticky notes, guided reading by yellow sticky notes, independent reading by green sticky notes, etc. Now do the math! Figure out a balance of instructional contexts that really works, in order to give your students a complete learning opportunity. You may only be able to teach guided reading three days a week in order to also read aloud three days a week and engage in shared reading three days a week. In fact, in some of the hybrid models teachers are grappling with right now, you may have to really narrow the amount of time you spend on each instructional context in order to teach all of them. This is, of course, less than ideal, but most of us don't get to decide the limitations on our instructional schedule, only how we spend the time within it. While these kinds of trade-offs may seem scary (and they are when you are trying to teach five instructional contexts in thirty minutes!) they can actually make you more efficient and give you some relief from the guilt of never feeling as if you can fit "it" all in. As you experiment with this shift, you may discover, for example, that much of what you previously accomplished in guided reading may be more efficiently taught in shared. Or you may find that you were teaching every student in small-groups when some don’t need that level of scaffolding. Once you have a week's schedule arranged, look at it as a whole. How balanced are the colors? Of course, this isn’t a rigid strategy. The time doesn’t have to be divided up into exactly equal portions. Things will vary based on the age of children, the point in the school year, etc. In general, however, does the schedule look relatively balanced and relatively complete? Implementation

Once you have a plan, you face the challenge of implementation. Of course, your schedule will vary from day-to-day. Now really concentrate on working within the timeframes. Use an egg timer and stop when you had planned to. This is really challenging, but if you do it a few times you will begin to really think about instructional time. If you know that you can’t run over the allotted time for guided reading, you will find ways to stay on schedule. Also, planning to stop, even if you aren’t finished, means that read aloud, independent reading, etc. don’t get neglected. Of course, this is not meant to be a militaristic implementation. I am not suggesting you teach robotically or become a rigidly driven by the clock. I am suggesting, however, that if you want to fit everything in, you will have to do a bit less of some things and a bit more of others. These kinds of changes in practice requires a shift from the frustrating mental model of fitting everything in every day. You can begin developing a new, kinder mental model with a few pads of sticky notes and an egg timer. Adapted from a blog post originally written by Jan Burkins and Kim Yaris.

2 Comments

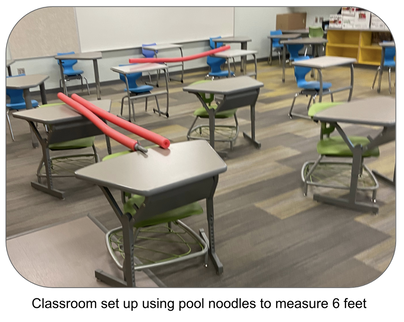

As educators all over the United States grapple with the back-to-school models that inevitably include simultaneous preparation for “face-to-face” learning and distance learning, there is an understandable sense of overwhelm. Teachers are faced with preparing for two different (or hybrid) and complicated learning environments. Not knowing which model will finally play out adds a distressing element of uncertainty. Perhaps, however, shifting our mental model can help. We can reframe the two options --”face-to-face” vs. remote learning-- as variations of distance learning, rather than as two completely different models. Then, we can find commonalities between them and start our planning there. Rather than thinking of back-to-school as either face-to-face or at-a-distance, in actuality, everything is going to be distance learning, even when students are in classrooms and “face-to-face.” As I’ve been thinking through what fall instruction can look like, it has been helpful to stop thinking of it as two different options, and to frame both options as variations of the same theme. Both are distance learning, with one six feet apart and the other miles apart. So I can plan for instruction that helps me with both at once. Here are some examples:

There aren’t easy answers to the complexities of back-to-school 2020, and the overwhelm we are all feeling is warranted. For me, however, as I think about how to support the teachers with whom I work, things became a bit unstuck when I stopped thinking about the home learning and school learning options as separate. It is all distance learning, friends, so perhaps we can begin planning accordingly. |

AuthorDr. Jan Burkins is a full-time writer, consultant, and professional development provider. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed