|

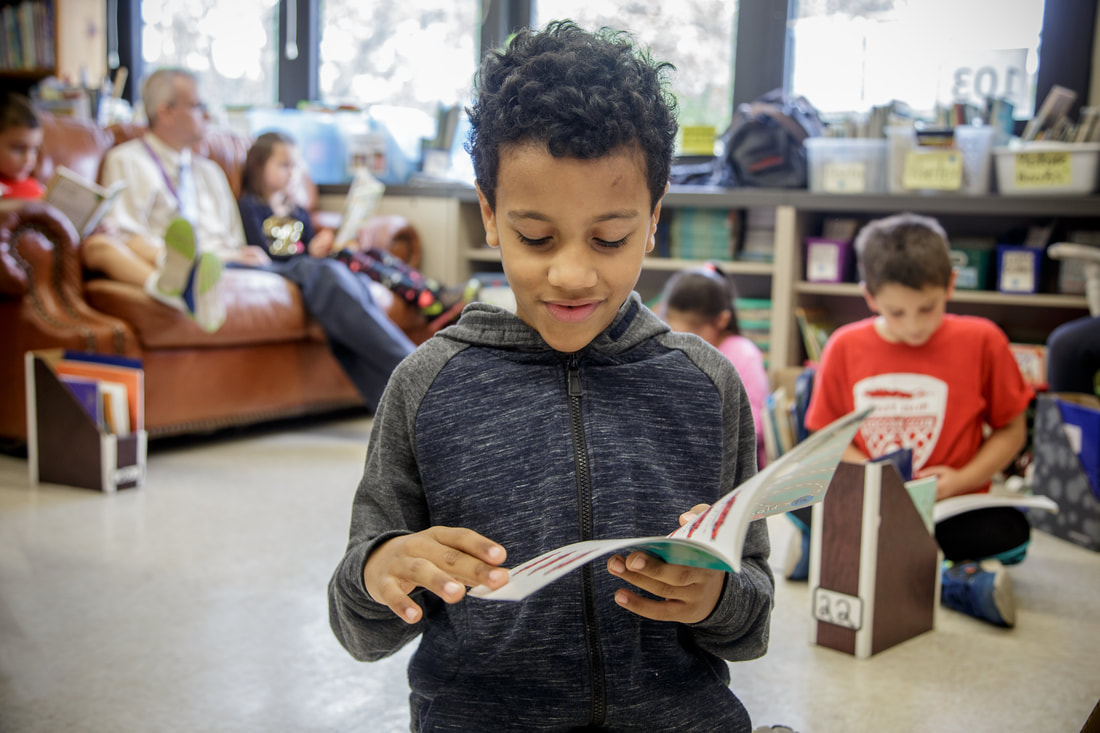

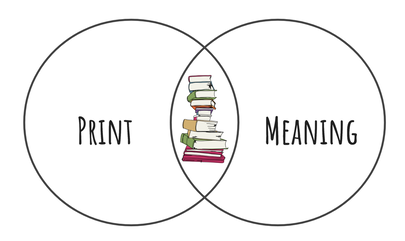

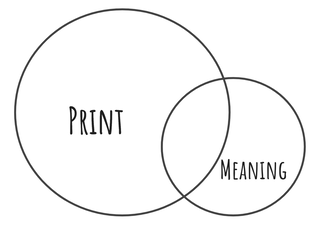

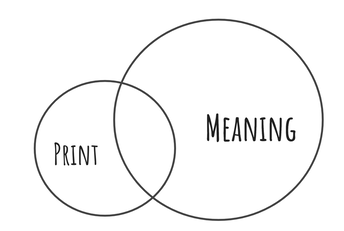

As educators, our ultimate goal, of course, is for readers to be equally proficient in navigating the print and in comprehending what they read. In fact, the more we understand about how individual children are doing these two things, the better we can teach them. So the reading process of a proficient reader can be generally represented like this: I first represented the print/meaning duality with with this two-circle Venn Diagram when I was a regional language arts consultant in 1999, because I wanted all of the work I did with teachers anchored in understandings of children's reading processes. Literally every workshop I've ever taught across two decades, has been held up by this mental model. Of course, not all children are equally proficient in both print and meaning, and variations on the Venn diagram can illustrate some of the differences. For example, children who are skilled in decoding but don't comprehend well, are represented with the same two circles, but the meaning circle is smaller. This reduction indicates that the stronger proficiency is in the area of decoding/word recognition, like this: Children with "small meaning circles" have difficulty with language comprehension. Their spoken vocabulary, general knowledge, and/or facility with language structure are typically limited, which places a ceiling on their reading comprehension. Children who's reading looks like this may rely on context to figure out words with little or no attention to the letters on the page. Similarly, children who are not skilled with reading the words (vs. understanding the words), are represented with the opposite pair of asymmetrical circles: Children with "small print circles" have limited orthographic knowledge. They don't fully understand how our alphabetic code works. Consequently, if tricky words are not sufficiently supported by context (which happens increasingly as text gets more difficulty) they get really stuck.

You can read about this simplified model in Preventing Misguided Reading (Burkins and Croft, 2010), Reading Wellness (Burkins and Yaris 2014), and Who's Doing the Work? (Burkins and Yaris, 2016). There are a number of factors that contribute to children reading in ways that favor meaning or favor print, paying insufficient attention to the other source of information. The most troublesome cause, however, is us, their teachers. If our instruction is biased towards print or meaning, then it is possible for children to learn to rely on that source of information and neglect the other. This is, or course, unintentional. In the next post in this two-part series, I will describe one of the ways we can inadvertently teach children not to use the print or not to comprehend.

0 Comments

|

AuthorDr. Jan Burkins is a full-time writer, consultant, and professional development provider. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed