|

Like many of us, I have been eager to move past 2020 without really looking back. I usually enjoy beginning each New Year by reflecting on the past year's learning and shaping plans for the next. However, the idea of lingering in the residue of 2020 has been unappealing at best, horrifying at worst. Who really wants to reflect on one of the hardest year's ever?

To complicate the reflective work even more, I tend to judge myself for not having enough pain this year to even really give myself permission to grieve or process it. Certainly, many people have had it much worse than I have. I continue to live a life with much privilege. We do not have hunger or housing insecurity. While 2020 has been challenging professionally, I have managed to keep my work afloat enough to support us. And most significantly, I have not lost a loved one to COVID (or anything else) this year. So what do I really have to lament from 2020? My sweet friend, Krystle Cobran, author of The Brave Educator, once told me, "We have a tendency to compare pain." She went on to say that using someone else's pain to delegitimize our own only delays our healing. So I try to give myself permission to process my experiences, even when some part of my brain tells me that they aren't serious enough to warrant attention because someone else's pain is more. I have learned the truth, however, that I can't be of service to anyone if I haven't tended my own inner garden in ways that are loving. This means acknowledging my hurts and grieving my losses, even if they seem smaller than someone else's. So when another friend, Lizzie Merritt, mentioned that she had just finished her "annual year in review" process, I thought, "Wait a minute! Perhaps, this year needs to be looked at even more closely than usual, rather than boxed up and stored in the recesses of my psychological closet." Lizzie was kind enough to share with me a reflective tool she created for learning from a previous year and planning for a new one. What I love about Lizzie's work is that she seems to really find a balance between action and reflection, between listening to ourselves and engaging our power to move past our limitations. For example, Lizzie's book about willpower begins with recommendations about learning to meditate. Lizzie was kind enough to let me share her year-in-review tool. I found the reflective the process challenging. I was surprised by how tender I was and how much my weary inner self wanted to avoid the work of self-reflection. I worked through the process in four different sittings, which helped. Because my work has demanded so much focus this year, I didn't pick work as a category. Basically, I never need nudging to work more. Instead, I chose: Health and Fitness; Home/Physical Environment; and Fun and Leisure. All of these areas need some serious attention from me. In fact, when I got to "Fun and Leisure," I was stumped (Does working on a "fun" writing project count?). Here's some of what I learned from the whole reflective process:

So, while I have no interest in a repeat of 2020, now that it is almost behind me, I am grateful for what it is taught me. May 2021 bring everyone at least some small dose of "normal." May we be kind to ourselves as we process 2020's difficulties, and may or biggest growth work of this year the stay with us, propelling us to be our most powerful selves.

1 Comment

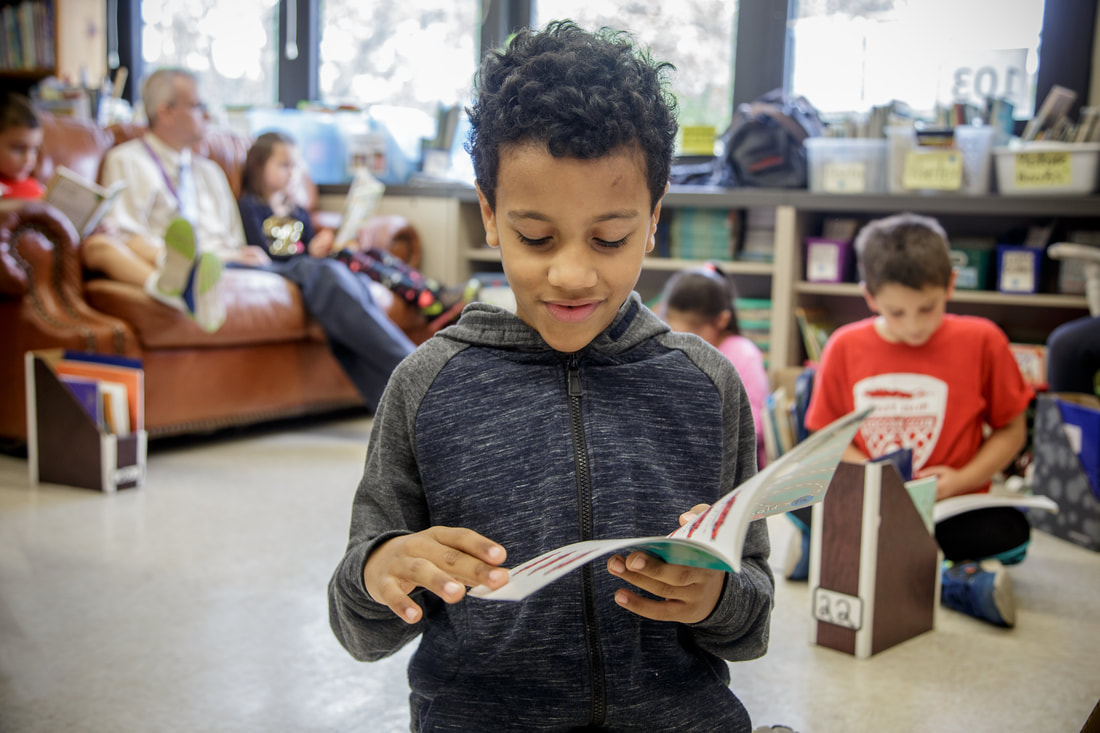

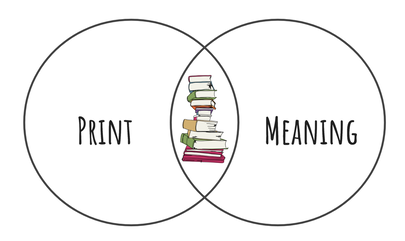

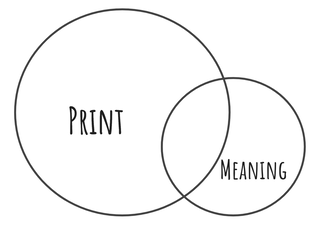

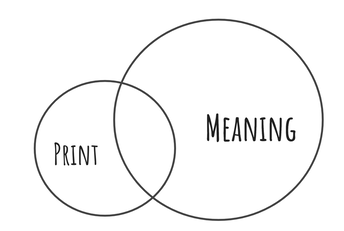

As educators, our ultimate goal, of course, is for readers to be equally proficient in navigating the print and in comprehending what they read. In fact, the more we understand about how individual children are doing these two things, the better we can teach them. So the reading process of a proficient reader can be generally represented like this: I first represented the print/meaning duality with with this two-circle Venn Diagram when I was a regional language arts consultant in 1999, because I wanted all of the work I did with teachers anchored in understandings of children's reading processes. Literally every workshop I've ever taught across two decades, has been held up by this mental model. Of course, not all children are equally proficient in both print and meaning, and variations on the Venn diagram can illustrate some of the differences. For example, children who are skilled in decoding but don't comprehend well, are represented with the same two circles, but the meaning circle is smaller. This reduction indicates that the stronger proficiency is in the area of decoding/word recognition, like this: Children with "small meaning circles" have difficulty with language comprehension. Their spoken vocabulary, general knowledge, and/or facility with language structure are typically limited, which places a ceiling on their reading comprehension. Children who's reading looks like this may rely on context to figure out words with little or no attention to the letters on the page. Similarly, children who are not skilled with reading the words (vs. understanding the words), are represented with the opposite pair of asymmetrical circles: Children with "small print circles" have limited orthographic knowledge. They don't fully understand how our alphabetic code works. Consequently, if tricky words are not sufficiently supported by context (which happens increasingly as text gets more difficulty) they get really stuck.

You can read about this simplified model in Preventing Misguided Reading (Burkins and Croft, 2010), Reading Wellness (Burkins and Yaris 2014), and Who's Doing the Work? (Burkins and Yaris, 2016). There are a number of factors that contribute to children reading in ways that favor meaning or favor print, paying insufficient attention to the other source of information. The most troublesome cause, however, is us, their teachers. If our instruction is biased towards print or meaning, then it is possible for children to learn to rely on that source of information and neglect the other. This is, or course, unintentional. In the next post in this two-part series, I will describe one of the ways we can inadvertently teach children not to use the print or not to comprehend. Navigating the Maze of Computerized Instruction: Problem-Solving Back-to-School 2020 (Post #2)7/26/2020 Before social distancing and home learning began in March, schools were already wrestling with the role that computers should play in classrooms. Whether weighing the decision to go to one-to-one devices for all students or navigating district mandates to use a certain program, reflective educators have long known that what makes technology helpful is the way it is used. But figuring out how to use it often means navigating a maze of mandates, program implications, and student needs. A couple of years ago, in one elementary school where I consulted, the district required that schools use a particular program to identify and address reading difficulties. I walked into a first-grade classroom in October to find about half of the first-graders working on iPads. They were using a computer program to learn phonemic awareness, letters, and sounds. Their iPad screens were filled with images of things like an apple, to which the narrator would say something like, “A is for apple. A says /a/.” It seemed strange to me that in October of first-grade so many students would need such rudimentary skills work. I asked the teacher about it. She said that all of her students had taken a placement test with the same computer program and that they were doing the lessons that the computer indicated they needed. I was skeptical. I asked the teacher if I could administer individual assessments with the students. When she agreed, I took each student out into the hall one at a time and administered Hearing and Recording Sounds, Marie Clay’s (2013) simple, first-grade assessment. Students had to write two connected sentences: I have a big dog at home. Today I am going to take him to school. Many of the students that the computer indicated should begin with lessons like, “Apple starts with A” were actually able to write the two sentences perfectly! Most of the other students were able to write reasonable sound-spellings for each of the phonemes in those sentences (e.g. skool for school). Every single child in the class already knew the sound for short A. I talked to the teacher. She explained that she was required to follow the directions of the computer program. I talked to the principal, who described the same district requirements and said there was no way to skip lessons in the program. All those children had to sit through all the very beginning reading lessons, even those who already knew all the letter sounds. Now that distance learning is the norm, reliance on large expensive programs to discern what children need--and to address those needs instructionally--seems to be on the rise. However, children actually need real teachers now more than ever. In a conversation with the literacy leadership in an elementary school where I am working throughout this school year (virtually and traveling by car when it is safe), they are dealing with district requirements to use a widespread monster program. They are frustrated, but they are trying to make it work for them. If you are trying to make the most of a required, comprehensive computer program, here are some things to consider:

In the end, computers can’t serve children well unless we use them well. Making the most of the tool you have been given, or even that you are required to use, means knowing that tool and knowing your students. This knowledge will help you maximize a program’s benefits while sidestepping it’s limitations, navigating the maze to your students' advantage. Clay, Marie M. (2013). An observation survey of early literacy achievement (3rd Ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. |

AuthorDr. Jan Burkins is a full-time writer, consultant, and professional development provider. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed