|

This year, even more than ever, you may be asking, "How do I fit it all in?!" We are, of course, in an unprecedented school year with abundant varieties of scheduling challenges. Whether you are teaching face-to-face or virtually, or in one of the million combinations of the two, you can work with even the trickiest of schedules by first stepping back to think about the big picture of your instruction. There are two common scheduling challenges that can compromise learning in your classroom, and both can be addressed with one, simple strategy. While the solution may not be perfect--there is no "perfect" solution to seeing children only once a week or having only 20 minutes for reading instruction--it will help you keep your focus on the overall goal of your literacy instruction--helping your students become proficient in the ways they navigate the print (phonemes and graphemes) and their ability to construct meaning. The reality is, you can’t fit "it all" in (and never could), as you are already aware--at least on some level. But each morning we begin the day and we try again to fit all the pieces into that six hours with students--or 3 hours, or 2 hours, or even 40 minutes! Inevitably, when our time is crunched, we end up cutting the same things because we have adopted the inaccurate belief that one instructional context is most important. We feel like word work is more important than read aloud, for example, so when the schedule is cut, so is read aloud. This means that our instruction is incomplete. Over time, this can form a pattern that undermines your efforts with students. In truth, your word work time will, in the long run, be much less beneficial for students if they don't get the glorious vocabulary building from read aloud. The second challenge is the temptation to search for a silver bullet or to put all your eggs in one basket; choose your cliche. The tendency to favor an instructional context makes us human, but fortunately we can be systematic in planning how we spend our instructional time. For example, usually when you ask someone who teaches guided reading how they teach reading, they respond by saying that they teach guided reading. The problem with such a response is that it shows an imbalance in instruction. Guided reading was never intended to be a program. It isn’t the core. Guided reading was designed as part of a larger context, which includes independent reading, shared reading, read aloud, and word work. Guided reading is not more important than these other pieces. The tendency is to set up guided reading and let the other pieces fall into place as they do, if they do. A relatively simple (albeit not perfect) solution to both problems of incompleteness and imbalance--which are really just two sides of the same coin--is to plan the instructional week rather than the instructional day. Practically speaking, you can plan with sticky notes and we implement with an egg timer. Planning Assign a sticky notes of a different color to each of the instructional contexts you want to include in your classroom. For example, shared reading may be represented by pink sticky notes, guided reading by yellow sticky notes, independent reading by green sticky notes, etc. Now do the math! Figure out a balance of instructional contexts that really works, in order to give your students a complete learning opportunity. You may only be able to teach guided reading three days a week in order to also read aloud three days a week and engage in shared reading three days a week. In fact, in some of the hybrid models teachers are grappling with right now, you may have to really narrow the amount of time you spend on each instructional context in order to teach all of them. This is, of course, less than ideal, but most of us don't get to decide the limitations on our instructional schedule, only how we spend the time within it. While these kinds of trade-offs may seem scary (and they are when you are trying to teach five instructional contexts in thirty minutes!) they can actually make you more efficient and give you some relief from the guilt of never feeling as if you can fit "it" all in. As you experiment with this shift, you may discover, for example, that much of what you previously accomplished in guided reading may be more efficiently taught in shared. Or you may find that you were teaching every student in small-groups when some don’t need that level of scaffolding. Once you have a week's schedule arranged, look at it as a whole. How balanced are the colors? Of course, this isn’t a rigid strategy. The time doesn’t have to be divided up into exactly equal portions. Things will vary based on the age of children, the point in the school year, etc. In general, however, does the schedule look relatively balanced and relatively complete? Implementation

Once you have a plan, you face the challenge of implementation. Of course, your schedule will vary from day-to-day. Now really concentrate on working within the timeframes. Use an egg timer and stop when you had planned to. This is really challenging, but if you do it a few times you will begin to really think about instructional time. If you know that you can’t run over the allotted time for guided reading, you will find ways to stay on schedule. Also, planning to stop, even if you aren’t finished, means that read aloud, independent reading, etc. don’t get neglected. Of course, this is not meant to be a militaristic implementation. I am not suggesting you teach robotically or become a rigidly driven by the clock. I am suggesting, however, that if you want to fit everything in, you will have to do a bit less of some things and a bit more of others. These kinds of changes in practice requires a shift from the frustrating mental model of fitting everything in every day. You can begin developing a new, kinder mental model with a few pads of sticky notes and an egg timer. Adapted from a blog post originally written by Jan Burkins and Kim Yaris.

2 Comments

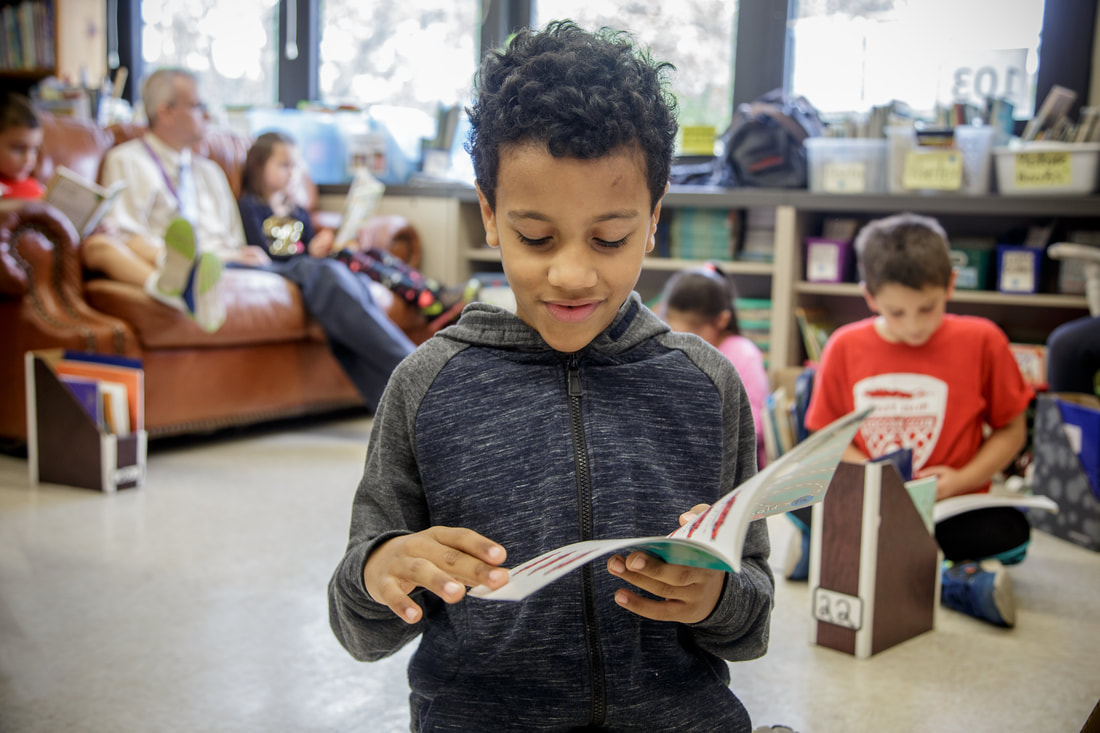

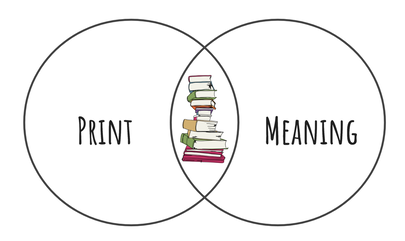

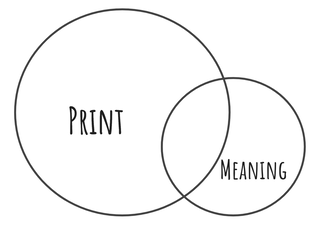

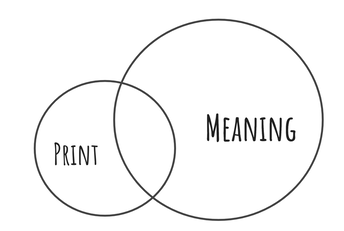

As educators, our ultimate goal, of course, is for readers to be equally proficient in navigating the print and in comprehending what they read. In fact, the more we understand about how individual children are doing these two things, the better we can teach them. So the reading process of a proficient reader can be generally represented like this: I first represented the print/meaning duality with with this two-circle Venn Diagram when I was a regional language arts consultant in 1999, because I wanted all of the work I did with teachers anchored in understandings of children's reading processes. Literally every workshop I've ever taught across two decades, has been held up by this mental model. Of course, not all children are equally proficient in both print and meaning, and variations on the Venn diagram can illustrate some of the differences. For example, children who are skilled in decoding but don't comprehend well, are represented with the same two circles, but the meaning circle is smaller. This reduction indicates that the stronger proficiency is in the area of decoding/word recognition, like this: Children with "small meaning circles" have difficulty with language comprehension. Their spoken vocabulary, general knowledge, and/or facility with language structure are typically limited, which places a ceiling on their reading comprehension. Children who's reading looks like this may rely on context to figure out words with little or no attention to the letters on the page. Similarly, children who are not skilled with reading the words (vs. understanding the words), are represented with the opposite pair of asymmetrical circles: Children with "small print circles" have limited orthographic knowledge. They don't fully understand how our alphabetic code works. Consequently, if tricky words are not sufficiently supported by context (which happens increasingly as text gets more difficulty) they get really stuck.

You can read about this simplified model in Preventing Misguided Reading (Burkins and Croft, 2010), Reading Wellness (Burkins and Yaris 2014), and Who's Doing the Work? (Burkins and Yaris, 2016). There are a number of factors that contribute to children reading in ways that favor meaning or favor print, paying insufficient attention to the other source of information. The most troublesome cause, however, is us, their teachers. If our instruction is biased towards print or meaning, then it is possible for children to learn to rely on that source of information and neglect the other. This is, or course, unintentional. In the next post in this two-part series, I will describe one of the ways we can inadvertently teach children not to use the print or not to comprehend. In my consulting work, I have pulled up alongside far too many beginning readers who--having been taught to read in explicit phonics programs--have inadvertently learned to neglect the meaning of what they are reading. They tend to deliberate laboriously in decoding a word--yes, an important process for beginning readers--when the context and the syntax could have confirmed their efforts and taken them from their phonetic approximation to the actual word. This is what the balanced literacy folks (and I count myself among them), refer to as “word callers.” This pattern of inattention to meaning--which leads to opportunity costs in teaching children that reading is about constructing meaning--is a legitimate problem with explicit phonics instruction.

On the other hand, I have pulled up alongside far too many beginning readers who--having been taught to read in a balanced literacy framework--have inadvertently learned to over rely on context as they problem-solve words. They often scour the picture for clues to words they could easily decode relying almost exclusively on context and moving on without looking closely at the print. This is what the phonics folks (and I count myself among them), refer to as “guessing.” This pattern of inattention to the print--which leads to opportunity costs in learning orthography--is a legitimate problem with balanced literacy. It often seems that, on either side of this debate, there is only noise and anger. There are, however, very reasonable and thoughtful folks exploring the nuances of each perspective and trying to actually listen closely to the voices of others. This can be difficult for many of us, however, myself included. Usually, this difficulty arises from the stories we tell ourselves...stories that aren't completely true. Before we make sweeping generalizations about an entire group of people--people who represent a range of ideas within a larger, general perspective--perhaps we can interrogate our beliefs about these people. To support this effort, I share The Work from Byron Katie, which is a five-step process for considering the ways our thinking tends to be biased towards self-preservation and protection of our egos. Step 1: If something someone says or does causes you distress, identify the underlying story/belief you are telling yourself, such as Balanced literacy folks do not believe in teaching students explicit or systematic phonics. OR Science of reading folks do not care if children learn to comprehend. OR Balanced literacy folks believe that learning to read is as easy as learning to talk. OR Science of reading folks don’t care if children read from dreary books and learn to hate reading. Step 2: Ask yourself if this belief is actually true. Your ego may jump up here and try to assert how accurate these extreme, negative statements are. Don’t overlook the ego’s need to be right, even at the expense of ourselves, our children, our relationships, etc. Perhaps you immediately recognize that these statements aren’t absolutely true. If so, skip step three. If you are still convinced that the statements above are absolutely true, then you will want to check out step three. Step 3: Go deeper. Ask yourself if the statement is absolutely true? Are there any exceptions? Could there be places where this belief doesn’t hold up? Do you know anyone who appreciates the contributions of the "science of reading" and also has demonstrated a clear commitment to student engagement and great texts? Do you know anyone who ascribes to "balanced literacy" who is intentional about phonics instruction? Of course, if you are honest with yourself (and you must be), you will recognize that there are circumstances where these statements are not true. Step 4: Think about how the negative belief affects you. Who are you when you believe this? How do you act? What do you say? How do you feel? Consider who you would be without this belief. Would you be more open to possibilities? Would you be better able to listen? Would you be able to focus on and expand what is working? Would you be better able to find opportunities for connection? Would you judge others less? Would you judge yourself less? Step 5: Flip the statements and see if you can persuade your ego that these new statements are at least somewhat true, if not absolutely true. Balanced literacy folks believe in teaching students explicit or systematic phonics. OR Science of reading folks care if children learn to comprehend. OR Balanced literacy folks don’t believe that learning to read is as easy as learning to talk. OR Science of reading folks care if children learn to hate reading. Notice the shift in your breathing and in your body tension as you actually step into the truth of these flipped statements. If you can believe in at least the possibility of these statements, despite the fact that you may have encountered some folks who seem to embody the opposites, then you are on your way. And then, if you want to move to ninja-level honesty, you can flip the statements in another way and consider the truth in them. For example, Science of reading folks do not believe in teaching students explicit or systematic phonics. (Children in classrooms with explicit phonics programs can learn the elements of the print system without learning how to apply them independently, in context. In fact, this problem is pretty widespread.) Balanced literacy folks do not care if children learn to comprehend. (Children in balanced literacy classrooms can also develop issues with comprehension. In fact, this problem is pretty widespread.) What does this extreme switch do to your perspective? Can we make space for the nuances within the perspectives with which we align? These latter points are an extreme, but they illustrates the ways that we construct realities that support our belief systems. Looking at the issues in the perspectives with which you align is important, honest work that is well within the scope of our individual power. You will accomplish more in addressing these issues than in engaging in angry debates where both sides are so triggered that no one can hear anyone else or look honestly at themselves. Until we consider the truth of the first set of flipped statements (i.e., Balanced literacy folks believe in teaching students explicit or systematic phonics; Science of reading folks care if children learn to comprehend.) we will find it difficult to actually hear each other and work together on behalf of children. The takeaways here are these:

When “The Science of Reading” community says that there are decades of research on early literacy instruction, I see the truth in this statement. Almost twenty years ago I wrote a dissertation entitled “A Meta-analysis of Phonological Awareness.” At that point in the history of literacy instruction, there were already mounds of research on the topic, enough to warrant a statistical summary of the data, which is something of a litmus test for the robustness of an area of inquiry.

The research was well received by the small audience that read it. It was one of three finalist for the International Reading Association’s (currently International Literacy Association) coveted Dissertation of the Year Award, and it won the Dissertation of the Year Award for the school of education at the University of Kansas where I was graduating. One unsurprising result of the study was that you could teach students to be phonologically aware and that this instruction improved students’ reading acquisition. In fact, one could say that you really don’t need to teach students phonological awareness unless you want them to learn how to read. Teaching phonological awareness is that important. Not teaching phonological awareness would be like suggesting that one couldn’t learn to swim without getting into some water. The second result, the one that excited my advisors, was that, while instruction in phonological awareness was critical to early literacy, one could get too much instruction in the area. After a student was sufficiently phonologically aware, continued instruction in hearing sounds within words didn’t just lend no further improvement, it produced an inhibitory effect. In other words, phonological awareness development is essential, but too much of it can actually impede progress. A meta-analysis is a statistical summary of all the statistical research on a topic. In designing a meta-analysis, one must decide whether to include unpublished dissertations. Unlike later meta-analyses of phonological awareness, I chose to include dissertations in my data, which meant that unpublished results were included. I did this to compensate for the publishing world’s bias towards positive results. Perhaps this is why I discovered some potential problems with phonological awareness instruction. In the later (and even current) phonological frenzy, I cringed to see whole classes of third-graders engaged explicit and isolated phonological awareness practice. I never published these results in a journal, partly because I had toddler twin sons, partly because I knew I wanted to remain a practitioner rather than an academician, partly because I was sick of the topic, and partly because I received a phone call from Linnea Ehri (who's work I was studying) who was also working on a meta-analysis of the phonological awareness research. But these findings have informed my lifetime of work in literacy and have been part of what has driven me to hold tight to systematic instruction in phonological awareness with a balanced perspective of not overdoing it. On one side of the current (and historical) debate, it is easy for phonological awareness instruction to be spotty and random, if at all, which I have continued to see as problematic even when mine wasn’t a popular perspective among some in the “balanced literacy” community. On the other side of the debate, it is easy for phonological awareness instruction to be overdone, which I have also continued to see as problematic even when perspective was unpopular among “the science of reading” community (even before it was called that). If you are convinced that something is THE key to literacy, whether contextualizing work with sounds and the print system that lays over them or explicitly teaching students the bits and pieces of our orthographic system, be careful not to push this certainty to extremes such that your reasonable conviction (and both convictions are reasonable) becomes the Achilles heel of your instruction. |

AuthorDr. Jan Burkins is a full-time writer, consultant, and professional development provider. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed