|

This year, even more than ever, you may be asking, "How do I fit it all in?!" We are, of course, in an unprecedented school year with abundant varieties of scheduling challenges. Whether you are teaching face-to-face or virtually, or in one of the million combinations of the two, you can work with even the trickiest of schedules by first stepping back to think about the big picture of your instruction. There are two common scheduling challenges that can compromise learning in your classroom, and both can be addressed with one, simple strategy. While the solution may not be perfect--there is no "perfect" solution to seeing children only once a week or having only 20 minutes for reading instruction--it will help you keep your focus on the overall goal of your literacy instruction--helping your students become proficient in the ways they navigate the print (phonemes and graphemes) and their ability to construct meaning. The reality is, you can’t fit "it all" in (and never could), as you are already aware--at least on some level. But each morning we begin the day and we try again to fit all the pieces into that six hours with students--or 3 hours, or 2 hours, or even 40 minutes! Inevitably, when our time is crunched, we end up cutting the same things because we have adopted the inaccurate belief that one instructional context is most important. We feel like word work is more important than read aloud, for example, so when the schedule is cut, so is read aloud. This means that our instruction is incomplete. Over time, this can form a pattern that undermines your efforts with students. In truth, your word work time will, in the long run, be much less beneficial for students if they don't get the glorious vocabulary building from read aloud. The second challenge is the temptation to search for a silver bullet or to put all your eggs in one basket; choose your cliche. The tendency to favor an instructional context makes us human, but fortunately we can be systematic in planning how we spend our instructional time. For example, usually when you ask someone who teaches guided reading how they teach reading, they respond by saying that they teach guided reading. The problem with such a response is that it shows an imbalance in instruction. Guided reading was never intended to be a program. It isn’t the core. Guided reading was designed as part of a larger context, which includes independent reading, shared reading, read aloud, and word work. Guided reading is not more important than these other pieces. The tendency is to set up guided reading and let the other pieces fall into place as they do, if they do. A relatively simple (albeit not perfect) solution to both problems of incompleteness and imbalance--which are really just two sides of the same coin--is to plan the instructional week rather than the instructional day. Practically speaking, you can plan with sticky notes and we implement with an egg timer. Planning Assign a sticky notes of a different color to each of the instructional contexts you want to include in your classroom. For example, shared reading may be represented by pink sticky notes, guided reading by yellow sticky notes, independent reading by green sticky notes, etc. Now do the math! Figure out a balance of instructional contexts that really works, in order to give your students a complete learning opportunity. You may only be able to teach guided reading three days a week in order to also read aloud three days a week and engage in shared reading three days a week. In fact, in some of the hybrid models teachers are grappling with right now, you may have to really narrow the amount of time you spend on each instructional context in order to teach all of them. This is, of course, less than ideal, but most of us don't get to decide the limitations on our instructional schedule, only how we spend the time within it. While these kinds of trade-offs may seem scary (and they are when you are trying to teach five instructional contexts in thirty minutes!) they can actually make you more efficient and give you some relief from the guilt of never feeling as if you can fit "it" all in. As you experiment with this shift, you may discover, for example, that much of what you previously accomplished in guided reading may be more efficiently taught in shared. Or you may find that you were teaching every student in small-groups when some don’t need that level of scaffolding. Once you have a week's schedule arranged, look at it as a whole. How balanced are the colors? Of course, this isn’t a rigid strategy. The time doesn’t have to be divided up into exactly equal portions. Things will vary based on the age of children, the point in the school year, etc. In general, however, does the schedule look relatively balanced and relatively complete? Implementation

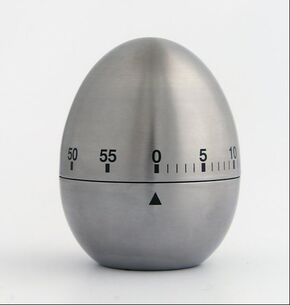

Once you have a plan, you face the challenge of implementation. Of course, your schedule will vary from day-to-day. Now really concentrate on working within the timeframes. Use an egg timer and stop when you had planned to. This is really challenging, but if you do it a few times you will begin to really think about instructional time. If you know that you can’t run over the allotted time for guided reading, you will find ways to stay on schedule. Also, planning to stop, even if you aren’t finished, means that read aloud, independent reading, etc. don’t get neglected. Of course, this is not meant to be a militaristic implementation. I am not suggesting you teach robotically or become a rigidly driven by the clock. I am suggesting, however, that if you want to fit everything in, you will have to do a bit less of some things and a bit more of others. These kinds of changes in practice requires a shift from the frustrating mental model of fitting everything in every day. You can begin developing a new, kinder mental model with a few pads of sticky notes and an egg timer. Adapted from a blog post originally written by Jan Burkins and Kim Yaris.

2 Comments

Sometimes, when we are trying to solve a problem we place limitations on ourselves because of tradition. We don't "think outside of the box" because we have come to consider the box as somehow integral to the process. It helps to sometimes bring to the foreground and scrutinize the barriers that we place on ourselves. So, what is limiting our thinking about guided reading, the trickiest instructional context to shift to digital platforms?

While read aloud, shared reading, and even independent reading and conferences seem to translate to virtual spaces with less disruption to the model, guided reading remains the more challenging instructional context to teach over a computer. In addition to the intrinsic challenge of teaching across cyberspace, the fact that probably no one else has your school district's exact model makes it harder to crowdsource the problems. I am endlessly amazed by all the different ways districts give shape to teaching in 2020 (and soon 2021). In this blog, Hacks for Virtual Guided Reading, I explored some intuitive suggestions for navigating guided reading in virtual spaces, including a suggestion for how to listen to individual students read during virtual guided reading. I recently worked with a school where a teacher was really problem-solving how do just this thing, but she needed a different solution than the one I offered in the previous blog. Her students all had access to district-provided laptops, so that eliminated one barrier that is present for some. In my conversation with the teacher, I realized that we were assuming some pre-virtual conditions that didn't necessarily have to apply. We found that adjusting away from those limitations helped us meet the goal of listening to students read instructional level texts, even though they weren't face to face. Here were some of our assumptions:

As it turns out, none of these assumptions is requisite to guided reading instruction. Questioning all of the aforementioned beliefs, we developed a plan. On Fridays, she is going to give her guided reading groups their texts via links placed on the school's virtual platform. Over the weekend, students will record themselves reading using either video, or simply audio. Students will send their teacher their recordings by Monday. During the week, she will listen to a few student recordings each day, as she had done when guided reading was face-to-face, and take running records. If a student is having difficulty, she will check in with that student via whatever tool seems appropriate. When the group gets together to talk about the book, they can engage in some choral reading of the text and have conversations about it. Again, there are things about this variation on the guided reading model that don't work as well as face-to-face guided reading. You may or may not find out how a child navigates a first-read in a text, although you may be able to specify that you want a first read in the directions. Either way, there are worse problems than a child practicing a text to sound good when they read it to you. If children see their recordings as something to practice and perfect, what we lose in cold-read data we gain in repeated readings practice and reading growth. There remains a driving need to work with small groups in virtual spaces. While none of the creative solutions out there seem to be perfect, many of us are finding that a pandemic is a great time to embrace approximations and explore not being a perfectionist. If you explore this model or some aspect of it, I would love to hear about what you figure out. You can always reach me at [email protected], or you can leave a comment on this post. ThI recently saw a Twitter post that called for replacing asynchronous with "anytime" and synchronous with "real time." Certainly these words are a mouthful! Children are likely to love learning them, however, even young children.

Since learning to read words depends on hearing words and building our phonological lexicons (the brain's collection of every word we have ever heard), I really love the idea of children hearing the words synchronous and asynchronous and thinking about what they mean. Furthermore, synchronous and asynchronous are really juicy words when it comes to learning morphemes-- the smallest units of meaning in a language. Consider the morphemes in synchronous. syn = with, together chron = time ous = full of So synchronous literally means "full of time together." And then, adding a- to the beginning of synchronous illustrates that this prefix negates the term, as in "not full of time together." How fun is that?! And what a missed opportunity if we choose to replace them with "real time" and "anytime" instead! But wait, there's more. The most powerful benefit of children learning these two words and the morphemes that compose them is that these morphemes can help children later figure out other words built with the same parts. Such as, photosynthesis synchronize synergistic chronological synthesizer synonym synopsis anachronistic chronograph chronic delicious adventurous conscious The idea that learning a few morphemes and then repurposing them to build new words--kind of like the way my sons use Legos--is vocabulary learning magic. To teach children how to figure out words by using known parts is to truly empower them to do the work (and it is fun!). So, please, don't think of synchronous and asynchronous as terrible words that are too hard for children to learn. Think of them as invitations. Think of them as the powerful intersection between print and meaning, where reading process comes together. You don't have to water down the words you use with children, hampering the growth of their phonological lexicons. In fact, if we combine knowledge of morphemes with agentive vocabulary exploration during independent reading, the effects on vocabulary growth can be synergistic! |

AuthorDr. Jan Burkins is a full-time writer, consultant, and professional development provider. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed