|

This year, even more than ever, you may be asking, "How do I fit it all in?!" We are, of course, in an unprecedented school year with abundant varieties of scheduling challenges. Whether you are teaching face-to-face or virtually, or in one of the million combinations of the two, you can work with even the trickiest of schedules by first stepping back to think about the big picture of your instruction. There are two common scheduling challenges that can compromise learning in your classroom, and both can be addressed with one, simple strategy. While the solution may not be perfect--there is no "perfect" solution to seeing children only once a week or having only 20 minutes for reading instruction--it will help you keep your focus on the overall goal of your literacy instruction--helping your students become proficient in the ways they navigate the print (phonemes and graphemes) and their ability to construct meaning. The reality is, you can’t fit "it all" in (and never could), as you are already aware--at least on some level. But each morning we begin the day and we try again to fit all the pieces into that six hours with students--or 3 hours, or 2 hours, or even 40 minutes! Inevitably, when our time is crunched, we end up cutting the same things because we have adopted the inaccurate belief that one instructional context is most important. We feel like word work is more important than read aloud, for example, so when the schedule is cut, so is read aloud. This means that our instruction is incomplete. Over time, this can form a pattern that undermines your efforts with students. In truth, your word work time will, in the long run, be much less beneficial for students if they don't get the glorious vocabulary building from read aloud. The second challenge is the temptation to search for a silver bullet or to put all your eggs in one basket; choose your cliche. The tendency to favor an instructional context makes us human, but fortunately we can be systematic in planning how we spend our instructional time. For example, usually when you ask someone who teaches guided reading how they teach reading, they respond by saying that they teach guided reading. The problem with such a response is that it shows an imbalance in instruction. Guided reading was never intended to be a program. It isn’t the core. Guided reading was designed as part of a larger context, which includes independent reading, shared reading, read aloud, and word work. Guided reading is not more important than these other pieces. The tendency is to set up guided reading and let the other pieces fall into place as they do, if they do. A relatively simple (albeit not perfect) solution to both problems of incompleteness and imbalance--which are really just two sides of the same coin--is to plan the instructional week rather than the instructional day. Practically speaking, you can plan with sticky notes and we implement with an egg timer. Planning Assign a sticky notes of a different color to each of the instructional contexts you want to include in your classroom. For example, shared reading may be represented by pink sticky notes, guided reading by yellow sticky notes, independent reading by green sticky notes, etc. Now do the math! Figure out a balance of instructional contexts that really works, in order to give your students a complete learning opportunity. You may only be able to teach guided reading three days a week in order to also read aloud three days a week and engage in shared reading three days a week. In fact, in some of the hybrid models teachers are grappling with right now, you may have to really narrow the amount of time you spend on each instructional context in order to teach all of them. This is, of course, less than ideal, but most of us don't get to decide the limitations on our instructional schedule, only how we spend the time within it. While these kinds of trade-offs may seem scary (and they are when you are trying to teach five instructional contexts in thirty minutes!) they can actually make you more efficient and give you some relief from the guilt of never feeling as if you can fit "it" all in. As you experiment with this shift, you may discover, for example, that much of what you previously accomplished in guided reading may be more efficiently taught in shared. Or you may find that you were teaching every student in small-groups when some don’t need that level of scaffolding. Once you have a week's schedule arranged, look at it as a whole. How balanced are the colors? Of course, this isn’t a rigid strategy. The time doesn’t have to be divided up into exactly equal portions. Things will vary based on the age of children, the point in the school year, etc. In general, however, does the schedule look relatively balanced and relatively complete? Implementation

Once you have a plan, you face the challenge of implementation. Of course, your schedule will vary from day-to-day. Now really concentrate on working within the timeframes. Use an egg timer and stop when you had planned to. This is really challenging, but if you do it a few times you will begin to really think about instructional time. If you know that you can’t run over the allotted time for guided reading, you will find ways to stay on schedule. Also, planning to stop, even if you aren’t finished, means that read aloud, independent reading, etc. don’t get neglected. Of course, this is not meant to be a militaristic implementation. I am not suggesting you teach robotically or become a rigidly driven by the clock. I am suggesting, however, that if you want to fit everything in, you will have to do a bit less of some things and a bit more of others. These kinds of changes in practice requires a shift from the frustrating mental model of fitting everything in every day. You can begin developing a new, kinder mental model with a few pads of sticky notes and an egg timer. Adapted from a blog post originally written by Jan Burkins and Kim Yaris.

2 Comments

Sometimes, when we are trying to solve a problem we place limitations on ourselves because of tradition. We don't "think outside of the box" because we have come to consider the box as somehow integral to the process. It helps to sometimes bring to the foreground and scrutinize the barriers that we place on ourselves. So, what is limiting our thinking about guided reading, the trickiest instructional context to shift to digital platforms?

While read aloud, shared reading, and even independent reading and conferences seem to translate to virtual spaces with less disruption to the model, guided reading remains the more challenging instructional context to teach over a computer. In addition to the intrinsic challenge of teaching across cyberspace, the fact that probably no one else has your school district's exact model makes it harder to crowdsource the problems. I am endlessly amazed by all the different ways districts give shape to teaching in 2020 (and soon 2021). In this blog, Hacks for Virtual Guided Reading, I explored some intuitive suggestions for navigating guided reading in virtual spaces, including a suggestion for how to listen to individual students read during virtual guided reading. I recently worked with a school where a teacher was really problem-solving how do just this thing, but she needed a different solution than the one I offered in the previous blog. Her students all had access to district-provided laptops, so that eliminated one barrier that is present for some. In my conversation with the teacher, I realized that we were assuming some pre-virtual conditions that didn't necessarily have to apply. We found that adjusting away from those limitations helped us meet the goal of listening to students read instructional level texts, even though they weren't face to face. Here were some of our assumptions:

As it turns out, none of these assumptions is requisite to guided reading instruction. Questioning all of the aforementioned beliefs, we developed a plan. On Fridays, she is going to give her guided reading groups their texts via links placed on the school's virtual platform. Over the weekend, students will record themselves reading using either video, or simply audio. Students will send their teacher their recordings by Monday. During the week, she will listen to a few student recordings each day, as she had done when guided reading was face-to-face, and take running records. If a student is having difficulty, she will check in with that student via whatever tool seems appropriate. When the group gets together to talk about the book, they can engage in some choral reading of the text and have conversations about it. Again, there are things about this variation on the guided reading model that don't work as well as face-to-face guided reading. You may or may not find out how a child navigates a first-read in a text, although you may be able to specify that you want a first read in the directions. Either way, there are worse problems than a child practicing a text to sound good when they read it to you. If children see their recordings as something to practice and perfect, what we lose in cold-read data we gain in repeated readings practice and reading growth. There remains a driving need to work with small groups in virtual spaces. While none of the creative solutions out there seem to be perfect, many of us are finding that a pandemic is a great time to embrace approximations and explore not being a perfectionist. If you explore this model or some aspect of it, I would love to hear about what you figure out. You can always reach me at [email protected], or you can leave a comment on this post. Who's Doing the Work? (Burkins & Yaris, 2016) explores the ways we support students in problem-solving, especially if they are grappling with something that is really requiring them to think deeply and work hard. Right now, when so much about our instruction is different than usual, asking good questions is a reliable and familiar friend. Of course, we all know that asking higher-order questions can help children learn more. But, while asking "good" questions remains important in mask-to-mask and digital spaces, it's what we do after we ask the question that matters next. I recently encountered, however, a bit of research on math instruction that is making me think about the limits of these "good" questions. In a study that compared the way math teachers ask questions during math instruction, researchers found that only 1 in 5 questions required children to make deep connections across the content. This does not seem like big news; we are all aware of the need to ask more questions that push children to take the content they are learning to levels of analysis and connection. We also appreciate the important role that procedural questions ("low level") play when learning new information or processes. Certainly, it would be silly to try and make every question higher- order. What is most fascinating about the study mentioned in Range, however, is that in many cases, when better questions were asked, children still didn't get the opportunity to think deeply about the content. Rather than actually getting to do the work, they were given a series of "hints." So even though the work began with an invitation into deep thinking, their thinking was actually hampered during the process of answering the question. While 1/5 of questions in the study were high-level questions, requiring students to deeply process the content, students received hint after hint in the form of a low-level question. So, low-level, hint-giving questions, eliminated the value of the original, good question. Historically, in developing better questions for reading instruction, we put a lot of energy into thinking about levels of inquiry and Blooms Taxonomy. We craft the questions thoughtfully, but the moments after the initial question matter just as much as the question. In fact, with hint-giving through a series of low-level questions, a question such as, How do authors show the ways characters change over time? becomes no more thought-provoking or learning-inducing than a question like, Who is the main character? Fortunately, there is a magic bullet for letting our better questions do the work we intend for them to do. The simple practice for making the most of our good questions it to, quite simply, wait. Wait time is the critical complement to a good question, and it is proving even more tricky in virtual instruction. A few seconds can feel like forever when you are up close on a camera screen. Instructional time is somehow different in this new time-space-continuum. But just because it feels like forever, doesn't mean it actually is forever. In virtual instruction especially, and in light of the negative effects of "hint" giving to move things along, just giving students time to think remains essential. Now more than ever, the way we support students in answering questions is just as important as the question itself. Note: If you are in search of the free ebooks for guided reading, go to the "Free Books" tab, above. There are a number of challenges that make teaching guided reading tricky in virtual spaces. From access to books, to watching body language, sound issues, there are definitely some hurdles to get over. As we prepare to go back-to-school, one virtual guided reading challenge is prominent: figuring out how to listen in as individual students read without falling into a round-robin routine.

There is a solution that seems pretty simple. In fact, I think it is so simple that it has been hidden in plain sight. When we are face-to-face during guided reading and listening to individual readers, we want to hear ONLY the reader that is getting our attention, while we conduct a running record or engage in a conversation. Additionally, we don't want the readers who are NOT receiving our attention at that moment to listen in on our exchange with the student in our focus--for their sakes and for the sake of the student who is reading with us. To limit what we hear from the other students we can, of course, mute their microphones. To limit what they hear, we can simply ask them to turn their volume all the way down! This seemingly obvious solution allows us to stay in the group, rather than send students off into breakout rooms, which is clunky. Staying in the group by having the student you are listening to turn up the volume (while the others turn their volume down) allows you to keep that small-group feel to your virtual guided reading lessons. By staying in the group together, you can still watch the other students to see that they are engaged with the text. A little motion on the screen, should get the attention of everyone again. You can use a chat box, or even something as simple as a sign with a student's name on it, to let the group know who needs to turn their volume back up so you can read with the next student. As for access to books, there seem to be a few options.

In the end, shared reading and one-on-one conferring are likely to do more of the heavy-lifting in virtual literacy instruction. However, it is worth trying to figure out how to maintain some small group work for those students who really need it to succeed. Asking the other children to turn down their volume while you work with one child may be one way to make small group instruction work in virtual spaces.

A couple of years ago, Kim Yaris and I wrote a collection of guided reading books to go with the Who's Doing the Work? K-2 Lesson Sets (Stenhouse, 2018). Carnegie Learning has graciously agreed to let me share the fiction titles from this collection with you, here on this site.

There are 15 titles ranging from Level A to Level J. I have built flipbooks with each title, and embedded them here on the site. The text below, one of my favorite in the collection, is an example of the set-up for each book, and will show you how the flipbooks in the collection work. Missing Socks, like all the books in the collection, includes illustrations designed to engage students and deepen the story.

Here are some highlights from the collection:

Mindfulness:

There are three titles in the collection that relate to mindfulness. Happy (Level C) is about a little girl who is exploring different kinds of happiness, such as the calm happiness of a breeze vs. the palpable happiness of a surprise birthday party. Hurry Up, Slow Down (Level D) is about a little girl who is walking to school with her father and is caught up in the simple beauty around her. Finally, Everyday Beautiful (Level H) is about two boys who have been asked to find something beautiful. One boy overlooks the natural beauty around him while another shows him how simple things can be beautiful.

Shadows:

There are five titles in the collection that use science related to light and shadows to tell a story. They range in levels from C-J. We wrote these to align with science standards. If you teach light and shadows, you may find these texts a nice way to integrate your science content into your reading instruction.

The books are all in flipbook format and are free to use and share with children, but they require a password to access them. To get the password, complete the form below. When you hit submit, a password will pop up on the screen. Use that password in step 2 (below) to access the books.

If you already have the Who's Doing the Work? K-2 Lesson Sets, these digital versions of some of the books should be helpful. Although you don't need the lessons to use the books, if you are interested in the lessons that go with the books, they are available from Stenhouse Publishers. Navigating the Maze of Computerized Instruction: Problem-Solving Back-to-School 2020 (Post #2)7/26/2020 Before social distancing and home learning began in March, schools were already wrestling with the role that computers should play in classrooms. Whether weighing the decision to go to one-to-one devices for all students or navigating district mandates to use a certain program, reflective educators have long known that what makes technology helpful is the way it is used. But figuring out how to use it often means navigating a maze of mandates, program implications, and student needs. A couple of years ago, in one elementary school where I consulted, the district required that schools use a particular program to identify and address reading difficulties. I walked into a first-grade classroom in October to find about half of the first-graders working on iPads. They were using a computer program to learn phonemic awareness, letters, and sounds. Their iPad screens were filled with images of things like an apple, to which the narrator would say something like, “A is for apple. A says /a/.” It seemed strange to me that in October of first-grade so many students would need such rudimentary skills work. I asked the teacher about it. She said that all of her students had taken a placement test with the same computer program and that they were doing the lessons that the computer indicated they needed. I was skeptical. I asked the teacher if I could administer individual assessments with the students. When she agreed, I took each student out into the hall one at a time and administered Hearing and Recording Sounds, Marie Clay’s (2013) simple, first-grade assessment. Students had to write two connected sentences: I have a big dog at home. Today I am going to take him to school. Many of the students that the computer indicated should begin with lessons like, “Apple starts with A” were actually able to write the two sentences perfectly! Most of the other students were able to write reasonable sound-spellings for each of the phonemes in those sentences (e.g. skool for school). Every single child in the class already knew the sound for short A. I talked to the teacher. She explained that she was required to follow the directions of the computer program. I talked to the principal, who described the same district requirements and said there was no way to skip lessons in the program. All those children had to sit through all the very beginning reading lessons, even those who already knew all the letter sounds. Now that distance learning is the norm, reliance on large expensive programs to discern what children need--and to address those needs instructionally--seems to be on the rise. However, children actually need real teachers now more than ever. In a conversation with the literacy leadership in an elementary school where I am working throughout this school year (virtually and traveling by car when it is safe), they are dealing with district requirements to use a widespread monster program. They are frustrated, but they are trying to make it work for them. If you are trying to make the most of a required, comprehensive computer program, here are some things to consider:

In the end, computers can’t serve children well unless we use them well. Making the most of the tool you have been given, or even that you are required to use, means knowing that tool and knowing your students. This knowledge will help you maximize a program’s benefits while sidestepping it’s limitations, navigating the maze to your students' advantage. Clay, Marie M. (2013). An observation survey of early literacy achievement (3rd Ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Image credit: Image by Sumanley xulx from Pixabay One of the big challenges with wearing a mask is being heard and understood. This may be particularly problematic for "face-to-face" learning this fall, when children are necessarily very spread out. Reading aloud, for example, to a group that is widely spread throughout the room would have its own challenges without a mask. In the video below, I show you how to use a personal voice amplifier while wearing a mask. The microphone is not a perfect solution to the challenges of teaching while wearing a mask, but it seems to offer quite a bit of volume and clarity. I also think it will reduce the fatigue of trying to project your voice through a mask all day, perhaps making this tricky back-to-school a tiny bit easier. There are a number of these devices available online, and the one I have is not a particularly sophisticated piece of equipment. I was excited, however, to see how well it worked while wearing a mask. Here are a few tips:

EveWhen I am stressed (angry, afraid, nervous, etc.), I inadvertently hold my breath. In those moments, my husband will sometimes notice and ask, "Are you breathing, Babe?" At that point, I exhale with a rush of air and pay attention to what I am doing (and not doing) with my lungs! I am always struck by my unconscious response of holding my breath. Realizing that I often don't breathe when I most need to has led me to actually practice breathing. Perhaps this sounds silly. Breathing is automatic, right? Well, sort of. While we have natural rhythms to our breath, intentionally filling and emptying our lungs completely requires focus and practice. One of my favorite times to intentionally practice breathing is anytime I am waiting. Because I use technology to teach, I am regularly asking whole groups of adults to wait. To wait for a hiccup in the wifi. To wait for a video to load. To wait for a website to respond. In these moments I often teach breathing lessons. I just engage us all in taking several slow deep breaths. I am always startled by how satisfying such technology glitches can be, when a whole room full of teachers simultaneously tune into their breath. Everyone seems to realize just how much stress we carry with us, and we're to find an antidote that was literally under our noses. You too can use a technological pause as an opportunity to breathe deeply with your students. Inevitable tech hiccups can also offer spontaneous but regular practice of in-the-moment breathing routines in your classrooms. You can lay the groundwork for these incidental breathing lessons by launching the school year with a formal-ish breathing lesson. Conscious breathing is an antidote to worry, at a time when we can all find much to worry about. Even if it is a bit complicated by wearing masks, it is worth the effort. Here are a few books you might use to anchor your breathing lessons:  The Breathing Book by Christopher Willard and Olive Weisser, includes a series of exercises to help students become aware of their breath. It is so beautifully practical, and even includes a breathing practice where you sit and hold a book.  Breathe with Me: Using Breath to Feel Calm, Strong, and Happy by Miriam Gates refers to breathing as a "superpower." This book is so relatable for young children and includes specific breathing strategies to try in different situations.  I Am Peace: A Book of Mindfulness by Susan Verde and illustrated by Peter H. Reynolds, speaks to the relief that taking a breath offers in a moment of worry. It is a lovely text for introducing the idea that we can learn to manage our minds. I invite you to use one of these books to introduce children to the idea that they can intentionally use their breath to serve them in moments of worry. This year promises some stress and some technology hiccups--opportunities to practicing breathing. When there is so much that we can't control for our students, especially this year, teaching them a breathing routine offers them the seed of a habit that can serve them for their entire lives. And if you feel like you need to take a deep breath yourself, you might consider this book to help you get started. You can start now. Just breathe. ThI recently saw a Twitter post that called for replacing asynchronous with "anytime" and synchronous with "real time." Certainly these words are a mouthful! Children are likely to love learning them, however, even young children.

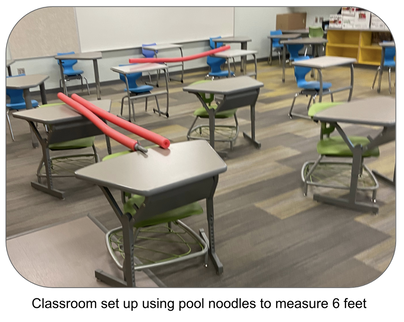

Since learning to read words depends on hearing words and building our phonological lexicons (the brain's collection of every word we have ever heard), I really love the idea of children hearing the words synchronous and asynchronous and thinking about what they mean. Furthermore, synchronous and asynchronous are really juicy words when it comes to learning morphemes-- the smallest units of meaning in a language. Consider the morphemes in synchronous. syn = with, together chron = time ous = full of So synchronous literally means "full of time together." And then, adding a- to the beginning of synchronous illustrates that this prefix negates the term, as in "not full of time together." How fun is that?! And what a missed opportunity if we choose to replace them with "real time" and "anytime" instead! But wait, there's more. The most powerful benefit of children learning these two words and the morphemes that compose them is that these morphemes can help children later figure out other words built with the same parts. Such as, photosynthesis synchronize synergistic chronological synthesizer synonym synopsis anachronistic chronograph chronic delicious adventurous conscious The idea that learning a few morphemes and then repurposing them to build new words--kind of like the way my sons use Legos--is vocabulary learning magic. To teach children how to figure out words by using known parts is to truly empower them to do the work (and it is fun!). So, please, don't think of synchronous and asynchronous as terrible words that are too hard for children to learn. Think of them as invitations. Think of them as the powerful intersection between print and meaning, where reading process comes together. You don't have to water down the words you use with children, hampering the growth of their phonological lexicons. In fact, if we combine knowledge of morphemes with agentive vocabulary exploration during independent reading, the effects on vocabulary growth can be synergistic! As educators all over the United States grapple with the back-to-school models that inevitably include simultaneous preparation for “face-to-face” learning and distance learning, there is an understandable sense of overwhelm. Teachers are faced with preparing for two different (or hybrid) and complicated learning environments. Not knowing which model will finally play out adds a distressing element of uncertainty. Perhaps, however, shifting our mental model can help. We can reframe the two options --”face-to-face” vs. remote learning-- as variations of distance learning, rather than as two completely different models. Then, we can find commonalities between them and start our planning there. Rather than thinking of back-to-school as either face-to-face or at-a-distance, in actuality, everything is going to be distance learning, even when students are in classrooms and “face-to-face.” As I’ve been thinking through what fall instruction can look like, it has been helpful to stop thinking of it as two different options, and to frame both options as variations of the same theme. Both are distance learning, with one six feet apart and the other miles apart. So I can plan for instruction that helps me with both at once. Here are some examples:

There aren’t easy answers to the complexities of back-to-school 2020, and the overwhelm we are all feeling is warranted. For me, however, as I think about how to support the teachers with whom I work, things became a bit unstuck when I stopped thinking about the home learning and school learning options as separate. It is all distance learning, friends, so perhaps we can begin planning accordingly. |

AuthorDr. Jan Burkins is a full-time writer, consultant, and professional development provider. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed