|

Dear Friends, For the last couple of weeks I have been making something for you. Inspired by my son's pen pal relationship this summer, I ordered every book I could find that involved characters who write letters. I read them all carefully, considering how some could work together around the theme, Mail Myself to You. Finally, I wrote a set of K-5 lessons--including Reading Art, Read Aloud, Shared Reading, Small Group Instruction, and Independent Reading. I've assembled these lessons in a tabbed hyperdoc--a pdf that links to sections within the document, as well as to sources outside the document. It includes videos of me describing the books and the lessons, written descriptions of each lesson, and ideas for extension. The lessons are clustered: kindergarten-1st, 2nd-3rd, and 4th-5th. The lessons are free, with a subscription to my blog/newsletter. If you complete the contact form below, I will email you personally, including the 25-page, linked PDF as an attachment (Please, give me 24 hours to respond). Or, if you want to write to me directly to request the document, my email is tct.jan@gmail.com. I am excited to share this collection of resources with you. They have been a labor of love. Wishing you all good things, Jan

18 Comments

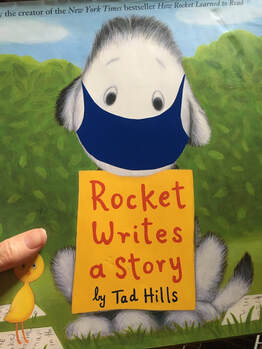

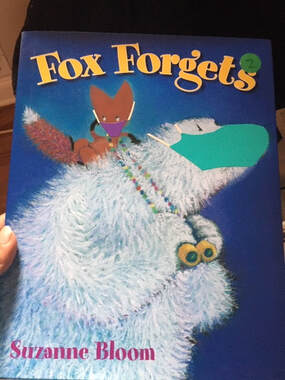

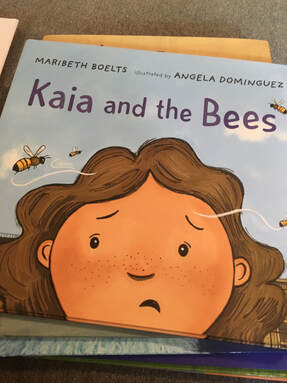

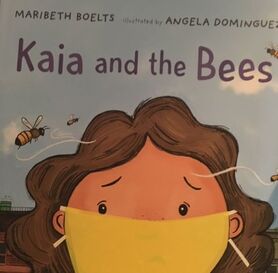

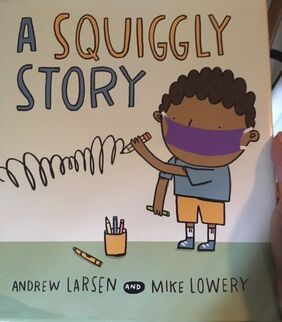

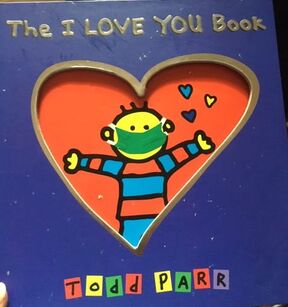

I've really been thinking about some of the ramifications of mask wearing, and wondering how to make them a little friendlier for young children. I decided it might soften mask wearing a bit if some of the characters on the front of picture books on the back-to-school shelf were wearing masks. For the most part, it was a pretty easy craft project for a rainy afternoon. All-in-all, it took me about 40 minutes to figure it out and apply masks to the characters on the covers of a handful of books. Here's what you will need:

Here's the process:

Here are a few images of the process: When I started this project, I just randomly picked titles that seemed to have characters on the cover that would were large enough to apply a mask on their faces. I was not picking books that were necessarily the best books for launching the school year, although some might be viable options.

While this is not a sophisticated or comprehensive solution to softening mask-wearing, it may prove a conversation starter or at least something to engage students. At the very least, this is a fun way to think about how masks can cover our expressions. You could even pull back the film to reveal the expressions of the characters. This project seems to be fun, whether you are sharing books virtually or in person. Perhaps, if you begin school "face-to-face," they should go on your shelf six-feet apart. Note: After I had completed the project, my children pointed out that the bird on Rocked Writes a Story didn't get masked! I had already put up my materials, at that point. If I were sharing the book with children, I would mask all of the characters on the cover. Navigating the Maze of Computerized Instruction: Problem-Solving Back-to-School 2020 (Post #2)7/26/2020 Before social distancing and home learning began in March, schools were already wrestling with the role that computers should play in classrooms. Whether weighing the decision to go to one-to-one devices for all students or navigating district mandates to use a certain program, reflective educators have long known that what makes technology helpful is the way it is used. But figuring out how to use it often means navigating a maze of mandates, program implications, and student needs. A couple of years ago, in one elementary school where I consulted, the district required that schools use a particular program to identify and address reading difficulties. I walked into a first-grade classroom in October to find about half of the first-graders working on iPads. They were using a computer program to learn phonemic awareness, letters, and sounds. Their iPad screens were filled with images of things like an apple, to which the narrator would say something like, “A is for apple. A says /a/.” It seemed strange to me that in October of first-grade so many students would need such rudimentary skills work. I asked the teacher about it. She said that all of her students had taken a placement test with the same computer program and that they were doing the lessons that the computer indicated they needed. I was skeptical. I asked the teacher if I could administer individual assessments with the students. When she agreed, I took each student out into the hall one at a time and administered Hearing and Recording Sounds, Marie Clay’s (2013) simple, first-grade assessment. Students had to write two connected sentences: I have a big dog at home. Today I am going to take him to school. Many of the students that the computer indicated should begin with lessons like, “Apple starts with A” were actually able to write the two sentences perfectly! Most of the other students were able to write reasonable sound-spellings for each of the phonemes in those sentences (e.g. skool for school). Every single child in the class already knew the sound for short A. I talked to the teacher. She explained that she was required to follow the directions of the computer program. I talked to the principal, who described the same district requirements and said there was no way to skip lessons in the program. All those children had to sit through all the very beginning reading lessons, even those who already knew all the letter sounds. Now that distance learning is the norm, reliance on large expensive programs to discern what children need--and to address those needs instructionally--seems to be on the rise. However, children actually need real teachers now more than ever. In a conversation with the literacy leadership in an elementary school where I am working throughout this school year (virtually and traveling by car when it is safe), they are dealing with district requirements to use a widespread monster program. They are frustrated, but they are trying to make it work for them. If you are trying to make the most of a required, comprehensive computer program, here are some things to consider:

In the end, computers can’t serve children well unless we use them well. Making the most of the tool you have been given, or even that you are required to use, means knowing that tool and knowing your students. This knowledge will help you maximize a program’s benefits while sidestepping it’s limitations, navigating the maze to your students' advantage. Clay, Marie M. (2013). An observation survey of early literacy achievement (3rd Ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Image credit: Image by Sumanley xulx from Pixabay One of the big challenges with wearing a mask is being heard and understood. This may be particularly problematic for "face-to-face" learning this fall, when children are necessarily very spread out. Reading aloud, for example, to a group that is widely spread throughout the room would have its own challenges without a mask. In the video below, I show you how to use a personal voice amplifier while wearing a mask. The microphone is not a perfect solution to the challenges of teaching while wearing a mask, but it seems to offer quite a bit of volume and clarity. I also think it will reduce the fatigue of trying to project your voice through a mask all day, perhaps making this tricky back-to-school a tiny bit easier. There are a number of these devices available online, and the one I have is not a particularly sophisticated piece of equipment. I was excited, however, to see how well it worked while wearing a mask. Here are a few tips:

EveWhen I am stressed (angry, afraid, nervous, etc.), I inadvertently hold my breath. In those moments, my husband will sometimes notice and ask, "Are you breathing, Babe?" At that point, I exhale with a rush of air and pay attention to what I am doing (and not doing) with my lungs! I am always struck by my unconscious response of holding my breath. Realizing that I often don't breathe when I most need to has led me to actually practice breathing. Perhaps this sounds silly. Breathing is automatic, right? Well, sort of. While we have natural rhythms to our breath, intentionally filling and emptying our lungs completely requires focus and practice. One of my favorite times to intentionally practice breathing is anytime I am waiting. Because I use technology to teach, I am regularly asking whole groups of adults to wait. To wait for a hiccup in the wifi. To wait for a video to load. To wait for a website to respond. In these moments I often teach breathing lessons. I just engage us all in taking several slow deep breaths. I am always startled by how satisfying such technology glitches can be, when a whole room full of teachers simultaneously tune into their breath. Everyone seems to realize just how much stress we carry with us, and we're to find an antidote that was literally under our noses. You too can use a technological pause as an opportunity to breathe deeply with your students. Inevitable tech hiccups can also offer spontaneous but regular practice of in-the-moment breathing routines in your classrooms. You can lay the groundwork for these incidental breathing lessons by launching the school year with a formal-ish breathing lesson. Conscious breathing is an antidote to worry, at a time when we can all find much to worry about. Even if it is a bit complicated by wearing masks, it is worth the effort. Here are a few books you might use to anchor your breathing lessons:  The Breathing Book by Christopher Willard and Olive Weisser, includes a series of exercises to help students become aware of their breath. It is so beautifully practical, and even includes a breathing practice where you sit and hold a book.  Breathe with Me: Using Breath to Feel Calm, Strong, and Happy by Miriam Gates refers to breathing as a "superpower." This book is so relatable for young children and includes specific breathing strategies to try in different situations.  I Am Peace: A Book of Mindfulness by Susan Verde and illustrated by Peter H. Reynolds, speaks to the relief that taking a breath offers in a moment of worry. It is a lovely text for introducing the idea that we can learn to manage our minds. I invite you to use one of these books to introduce children to the idea that they can intentionally use their breath to serve them in moments of worry. This year promises some stress and some technology hiccups--opportunities to practicing breathing. When there is so much that we can't control for our students, especially this year, teaching them a breathing routine offers them the seed of a habit that can serve them for their entire lives. And if you feel like you need to take a deep breath yourself, you might consider this book to help you get started. You can start now. Just breathe. ThI recently saw a Twitter post that called for replacing asynchronous with "anytime" and synchronous with "real time." Certainly these words are a mouthful! Children are likely to love learning them, however, even young children.

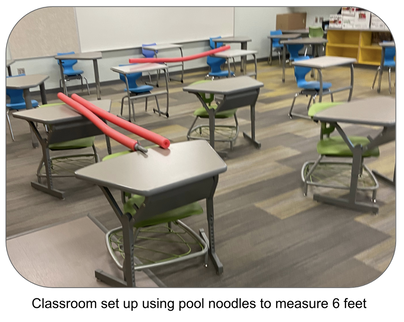

Since learning to read words depends on hearing words and building our phonological lexicons (the brain's collection of every word we have ever heard), I really love the idea of children hearing the words synchronous and asynchronous and thinking about what they mean. Furthermore, synchronous and asynchronous are really juicy words when it comes to learning morphemes-- the smallest units of meaning in a language. Consider the morphemes in synchronous. syn = with, together chron = time ous = full of So synchronous literally means "full of time together." And then, adding a- to the beginning of synchronous illustrates that this prefix negates the term, as in "not full of time together." How fun is that?! And what a missed opportunity if we choose to replace them with "real time" and "anytime" instead! But wait, there's more. The most powerful benefit of children learning these two words and the morphemes that compose them is that these morphemes can help children later figure out other words built with the same parts. Such as, photosynthesis synchronize synergistic chronological synthesizer synonym synopsis anachronistic chronograph chronic delicious adventurous conscious The idea that learning a few morphemes and then repurposing them to build new words--kind of like the way my sons use Legos--is vocabulary learning magic. To teach children how to figure out words by using known parts is to truly empower them to do the work (and it is fun!). So, please, don't think of synchronous and asynchronous as terrible words that are too hard for children to learn. Think of them as invitations. Think of them as the powerful intersection between print and meaning, where reading process comes together. You don't have to water down the words you use with children, hampering the growth of their phonological lexicons. In fact, if we combine knowledge of morphemes with agentive vocabulary exploration during independent reading, the effects on vocabulary growth can be synergistic! As educators all over the United States grapple with the back-to-school models that inevitably include simultaneous preparation for “face-to-face” learning and distance learning, there is an understandable sense of overwhelm. Teachers are faced with preparing for two different (or hybrid) and complicated learning environments. Not knowing which model will finally play out adds a distressing element of uncertainty. Perhaps, however, shifting our mental model can help. We can reframe the two options --”face-to-face” vs. remote learning-- as variations of distance learning, rather than as two completely different models. Then, we can find commonalities between them and start our planning there. Rather than thinking of back-to-school as either face-to-face or at-a-distance, in actuality, everything is going to be distance learning, even when students are in classrooms and “face-to-face.” As I’ve been thinking through what fall instruction can look like, it has been helpful to stop thinking of it as two different options, and to frame both options as variations of the same theme. Both are distance learning, with one six feet apart and the other miles apart. So I can plan for instruction that helps me with both at once. Here are some examples:

There aren’t easy answers to the complexities of back-to-school 2020, and the overwhelm we are all feeling is warranted. For me, however, as I think about how to support the teachers with whom I work, things became a bit unstuck when I stopped thinking about the home learning and school learning options as separate. It is all distance learning, friends, so perhaps we can begin planning accordingly. I used to carry a very large, leather purse. It was actually a glorified computer bag. I loved it because, when I traveled, I could just slip my computer into it and go. With my relatively slight frame, I looked like a child playing dress-up. It made my gate uneven as I leaned to the right with the weight of it. If I wasn’t careful, I could just walk in circles. Once, while waiting for my husband to run some errands downtown, I carried that giant purse into a local store to pass the time. I held some earrings up to my ears, caressed a camisole, and sniffed a candle, all before I realized that I was being followed. The sales clerk was not subtle or clever about the way she trailed behind me, pretending to straighten this or that. Once I realized that she assumed I was a shoplifter because of my big bag, I had to resist the urge to pitch a fit. To call her out in the store. To ask to speak to the manager. I didn’t do any of those things, but I have never been in that store since, and I don’t hesitate to tell the story to friends (chock full of can-you-believe-it-ness) whenever someone mentions that store. That was probably not the first sales clerk who looked suspiciously at my bag, which was more carry-on luggage than purse. Other clerks were probably just more discreet, or maybe I was just more clueless. I retired that purse. Now I carry something small--the opposite extreme, even. Something with room for a tissue and a throat lozenge. No one wants to be treated like a thief. But I keep thinking of that “incident,” and how offended I was to be considered a likely candidate for cramming a floral print dress into my bag. My husband, who is Black, has dealt with similar experiences his whole life (although he has never carried a big purse.) As many of us have, I have been thinking about social injustice and recent atrocities. It is easy to feel useless or clueless in all this. As a White person, or really just as a person, I don’t want to say or do the “wrong” thing. I know I’m not alone in this hesitancy. I recently saw a tweet where someone Black coached well-intentioned White people to take a list of other actions before asking a Black person to give them advice on how to be White right now. Our Black friends, who know how to talk us through all this stuff without us freaking out, can grow weary of us. So, as I’ve been measuring my words, hemming and hawing, trying to figure out what to do next because I want to do "something,” I didn’t immediately call on the educator friends of color that I usually turn to for advice. But eventually I broke down. I called a dear friend. I asked him how he was. He sighed heavily. He is on the frontline of educator conversations about race, and I could certainly imagine what was making him sigh at this point in history. But I was wrong. What is actually most frustrating for him at the moment is trying to help one well-intentioned White person after another sort through their feelings and their responsibilities. It’s giving them the tough or kind love they need to muster the courage to step out. And even though he is counselor to children, parents, and teachers as they work through the grief associated with murders, such as the killings of Rayshard Brooks, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor, he has done this grief work enough to know his way around it, as horrible as it is. But the needy White people, like me, are the thing that is exhausting for him right now. Lots of us have been spurred to action, but we just aren't sure what that action should be. And we want to take action the "right" way. And there I was, a whiny White woman on the phone asking him to tell me how to do the right thing. A woman who wants to pitch a fit because she feels she has the right to carry a purse large enough to steal a winter coat in without anyone assuming the worst of her. Someone calling for a pep talk because she’s afraid that she might be perceived as insensitive or racist or insight some fury on a social media platform. Heaven forbid. And he was his usual, generous self, of course, coaching me past looking for a way to be supportive enough without having to really put something on the line. In my consulting work, I have pulled up alongside far too many beginning readers who--having been taught to read in explicit phonics programs--have inadvertently learned to neglect the meaning of what they are reading. They tend to deliberate laboriously in decoding a word--yes, an important process for beginning readers--when the context and the syntax could have confirmed their efforts and taken them from their phonetic approximation to the actual word. This is what the balanced literacy folks (and I count myself among them), refer to as “word callers.” This pattern of inattention to meaning--which leads to opportunity costs in teaching children that reading is about constructing meaning--is a legitimate problem with explicit phonics instruction.

On the other hand, I have pulled up alongside far too many beginning readers who--having been taught to read in a balanced literacy framework--have inadvertently learned to over rely on context as they problem-solve words. They often scour the picture for clues to words they could easily decode relying almost exclusively on context and moving on without looking closely at the print. This is what the phonics folks (and I count myself among them), refer to as “guessing.” This pattern of inattention to the print--which leads to opportunity costs in learning orthography--is a legitimate problem with balanced literacy. It often seems that, on either side of this debate, there is only noise and anger. There are, however, very reasonable and thoughtful folks exploring the nuances of each perspective and trying to actually listen closely to the voices of others. This can be difficult for many of us, however, myself included. Usually, this difficulty arises from the stories we tell ourselves...stories that aren't completely true. Before we make sweeping generalizations about an entire group of people--people who represent a range of ideas within a larger, general perspective--perhaps we can interrogate our beliefs about these people. To support this effort, I share The Work from Byron Katie, which is a five-step process for considering the ways our thinking tends to be biased towards self-preservation and protection of our egos. Step 1: If something someone says or does causes you distress, identify the underlying story/belief you are telling yourself, such as Balanced literacy folks do not believe in teaching students explicit or systematic phonics. OR Science of reading folks do not care if children learn to comprehend. OR Balanced literacy folks believe that learning to read is as easy as learning to talk. OR Science of reading folks don’t care if children read from dreary books and learn to hate reading. Step 2: Ask yourself if this belief is actually true. Your ego may jump up here and try to assert how accurate these extreme, negative statements are. Don’t overlook the ego’s need to be right, even at the expense of ourselves, our children, our relationships, etc. Perhaps you immediately recognize that these statements aren’t absolutely true. If so, skip step three. If you are still convinced that the statements above are absolutely true, then you will want to check out step three. Step 3: Go deeper. Ask yourself if the statement is absolutely true? Are there any exceptions? Could there be places where this belief doesn’t hold up? Do you know anyone who appreciates the contributions of the "science of reading" and also has demonstrated a clear commitment to student engagement and great texts? Do you know anyone who ascribes to "balanced literacy" who is intentional about phonics instruction? Of course, if you are honest with yourself (and you must be), you will recognize that there are circumstances where these statements are not true. Step 4: Think about how the negative belief affects you. Who are you when you believe this? How do you act? What do you say? How do you feel? Consider who you would be without this belief. Would you be more open to possibilities? Would you be better able to listen? Would you be able to focus on and expand what is working? Would you be better able to find opportunities for connection? Would you judge others less? Would you judge yourself less? Step 5: Flip the statements and see if you can persuade your ego that these new statements are at least somewhat true, if not absolutely true. Balanced literacy folks believe in teaching students explicit or systematic phonics. OR Science of reading folks care if children learn to comprehend. OR Balanced literacy folks don’t believe that learning to read is as easy as learning to talk. OR Science of reading folks care if children learn to hate reading. Notice the shift in your breathing and in your body tension as you actually step into the truth of these flipped statements. If you can believe in at least the possibility of these statements, despite the fact that you may have encountered some folks who seem to embody the opposites, then you are on your way. And then, if you want to move to ninja-level honesty, you can flip the statements in another way and consider the truth in them. For example, Science of reading folks do not believe in teaching students explicit or systematic phonics. (Children in classrooms with explicit phonics programs can learn the elements of the print system without learning how to apply them independently, in context. In fact, this problem is pretty widespread.) Balanced literacy folks do not care if children learn to comprehend. (Children in balanced literacy classrooms can also develop issues with comprehension. In fact, this problem is pretty widespread.) What does this extreme switch do to your perspective? Can we make space for the nuances within the perspectives with which we align? These latter points are an extreme, but they illustrates the ways that we construct realities that support our belief systems. Looking at the issues in the perspectives with which you align is important, honest work that is well within the scope of our individual power. You will accomplish more in addressing these issues than in engaging in angry debates where both sides are so triggered that no one can hear anyone else or look honestly at themselves. Until we consider the truth of the first set of flipped statements (i.e., Balanced literacy folks believe in teaching students explicit or systematic phonics; Science of reading folks care if children learn to comprehend.) we will find it difficult to actually hear each other and work together on behalf of children. The takeaways here are these:

I recently had lunch with my dear mentor and she told me a story about working in a classroom and sitting with a first grade student who was just beginning to read. She asked him to share his independent reading book with her only to discover that it was much too hard for him to read on his own. They went together to the classroom library, which was beautifully organized by topic and areas of interest to the students. As it turned out, however, there was literally nothing in the classroom library that the reader could actually decode independently.

As you are assembling and organizing your classroom library consider the quality, the accessibility, and reading level of what is available to students. As Kim Yaris and I describe in Reading Wellness, at any given time students will be reading more than one text. For beginning readers, that should include variety in terms of difficulty. A single reader may have one or more picture books, which he or she may read by looking at the pictures and telling the story. Hopefully, he or she will also have some high-quality, controlled-vocabulary texts--decodable and/or patterned--to engage in the practice of decoding and constructing meaning. |

AuthorDr. Jan Burkins is a full-time writer, consultant, and professional development provider. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed